Bank of America’s Takeover of Merrill Lynch

Bank of America agreed to pay $2.43 billion to settle a class-action lawsuit with investors who owned or bought its shares when the bank purchased Merrill Lynch in 2008.  Bank of America acquired Merrill Lynch in late 2008 during the financial crisis. The $50 billion deal came as Merrill Lynch was within days of collapse, effectively rescuing it from bankruptcy. This settlement ended a three-year fight with a group of five plaintiffs, including the State Teachers Retirement System of Ohio and the Teacher Retirement System of Texas. They accused the bank and its officers of making false or misleading statements about the health of Bank of America and Merrill Lynch and were planning to seek $20 billion if the case went to trial. Bank of America denied these allegations and agreed to pay the settlement as a way of eliminating extended litigation.

Bank of America acquired Merrill Lynch in late 2008 during the financial crisis. The $50 billion deal came as Merrill Lynch was within days of collapse, effectively rescuing it from bankruptcy. This settlement ended a three-year fight with a group of five plaintiffs, including the State Teachers Retirement System of Ohio and the Teacher Retirement System of Texas. They accused the bank and its officers of making false or misleading statements about the health of Bank of America and Merrill Lynch and were planning to seek $20 billion if the case went to trial. Bank of America denied these allegations and agreed to pay the settlement as a way of eliminating extended litigation.

The Players:

- Bank of America: Bank of America Corporation is a bank holding and financial holding company. Its primary headquarters are located in Charlotte, North Carolina. Brian Moynihan is the current CEO, while Charles Holliday serves as chairman. Bank of America operates in 32 states, the District of Columbia, and more than 30 countries internationally. Bank of America functions through the “banks” in which they provide a variety of banking and non-banking financial services and products. As per 2011 financials, the shareholder’s equity was $232.50 billion.

- Ken Lewis: In 2008, when Bank of America took over, Ken Lewis was Merrill Lynch’s chairman and CEO.

- Merrill Lynch & Co.: Merrill Lynch was founded in 1914; it quickly became successful, specializing particularly in investment banking. The company continued to build its brokerage network and eventually became known as the “Thundering Herd.”

- John Thain: He was chairman and CEO of Merrill Lynch and was in this position for about nine months when he made this weekend deal with Bank of America.

- The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC): The SEC is a federal agency that acts as the primary enforcer of federal securities laws and regulates the securities industry, the nation’s stock exchanges, and other electronic securities markets in the United States. The SEC has the authority to bring civil enforcement actions against individuals or companies alleged to have violated the securities law.

- Government and Economy of the United States of America: From the government’s point of view, another major collapse of a Wall Street corporation would likely cause an enormous crisis in an already unstable financial climate. The overall economy of the United States was at risk; there were fears that a deep depression could result in untold damage to the citizens of the country. Even without total economic collapse, the taxpayers were certainly at risk in taking on the financial obligations of a failed Merrill Lynch.

- Board of Directors: The Board of Directors of Bank of America and Merrill Lynch were directly affected by the decision of not being transparent to the public and shareholders. Also, the information that the voters did not receive from Ken Lewis and John Thain allowed the acquisition to take place in such economic turmoil.

- Shareholders: Millions of shareholders of Bank of America would be affected by the decision and the consequences of an unfortunate takeover.

- Ben Bernanke: He was the Federal Reserve chairman who, according to Lewis, insisted that he did not back out of the deal.

Instruments:

After 2001, the real estate boom accelerated. To service this market, Wall Street created a number of financial instruments. These instruments were a major cause for the decline of Merrill Lynch.

Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDO): These instruments repackaged a pool of bonds, derivatives, and other instruments such as corporate bonds. The CDO derived its value from converting illiquid assets, such as buildings, into liquid financial instruments. A mortgage CDO bundled thousands of individual mortgages into a single bond, which was supposed to diversify default risk.

Mortgage-backed Securities: These are a subset of CDOs. They were bundles of mortgages that were sold to Fannie Mae, which repackaged them to sell as stock to individual investors. This process enabled banks to take mortgages off their balance sheets.

Credit Default Swaps (CDS): These were an insurance policy against the risk of investors, who bought them like bonds. A premium was paid to underwrite the risk of the various instruments like CDOs. CDSs lowered the cost of taking risks and created confidence in investors.

Events:

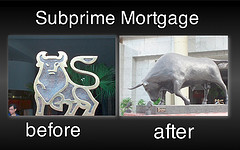

Risky Financial Instruments

In 2001, interest rates in the U.S. fell to low levels for several reasons. The environment of “cheap credit” encouraged investors and financial institutions to speculate in the real estate market, which increased property value and enticed household consumers to take additional debt. The Federal Reserve began to raise the interest rate incrementally in late 2004. By 2006, the subprime mortgage market began to appear vulnerable because of the increased interest rate. Holders of adjustable rate mortgages were required to make higher monthly payments than many could meet. The entire mortgage finance system, which was based on the assumption of ever-rising property value, began to unravel. Many rushed to sell their houses, which created further downward pressure on housing prices. This created a series of financial failures as CDOs dropped in value and banks lost their capital in defaults and withdrawals. In June 2007, two hedge funds managed by Bear Sterns suffered substantial losses and required huge capital injections from the bank, frightened investors, and investments bankers. These funds were heavily invested in high-risk, mortgage-backed securities and had been used to borrow more capital from the market.

BoA and Merrill Buy Damaging Assets

Countrywide Financials, which was America’s largest mortgage lender, had huge exposure in the subprime market. The company had approximately 900 offices and $200 billion in assets but was forced to draw down on its entire $11.5 billion credit line because of high exposure in the subprime market. Many regulators blamed Countrywide for helping fuel the housing bubble by offering loans to high-risk borrowers, so the company had very little hope of government help. Ken Lewis saw this as an opportunity to enhance the bank’s role in mortgage banking. Bank of America took a 16 percent stake in the company in August 2007, and there were hopes that this investment would bring some confidence in the market. But Countrywide’s stock collapsed, and Bank of America bought Countrywide with a total investment of $4.1billion.

Former Merrill Lynch CEO Stan O’Neal said that to generate higher returns, the firm would take on more risks. After entering the mortgage market by repackaging and selling home loans on the debt markets, Merrill Lynch acquired mortgage origination companies so collateral could be readily available. With AIG as its partner, Merrill Lynch became the largest issuer of CDOs. By the end of 2008, Merrill Lynch had issued CDOs worth $136 billion. In 2005, AIG had stopped insuring even the highest-rated CDOs issued by Merrill Lynch because of its aggressive underwriting policies, but Merrill Lynch continued to do what made the highest profits. When the subprime market slowed down, the entire CDO market unraveled. Merrill Lynch, like many others, did not record its position in the market, as the market and credit rating agencies had failed to anticipate the possibility of large-scale collapse in the housing market.

Merrill Lynch Suffers Monstrous Losses

In late 2007, when Merrill Lynch was forced to admit its liabilities of $7.9 billion and write off $9 billion in holdings, O’Neal was forced to resign, and John Thain took over as CEO. O’Neal was still allowed to retain his $30 million in retirement benefits and $129 million in stocks and options. John Thain also failed to understand the extent of Merrill Lynch’s financial condition, which he later acknowledged. But with further losses of $10 billion in CDOs in 2008, the bank was in serious trouble. With the support of the New York Federal Reserve Bank, Thain approached Bank of America CEO Ken Lewis to sell the company. Although Thain initially turned down the offer from Lewis, he sold Merrill Lynch for $50 billion, at $29 per share. The investment firm had more than $1.02 trillion in assets and more than 60,000 employees worldwide. Bank of America became more universal once it acquired Merrill Lynch. The primary concern for Bank of America was the actual worth of Merrill Lynch in 2008, when the market environment fluctuated rapidly. Lewis wanted to buy the company because of Merrill Lynch’s strongest unit, its 16,000 investment advisors, which would fill a hole in Bank of America’s product offering. The entire transaction took place in the panic when Lehman Brothers was about to declare bankruptcy.

BoA Buys Merrill Lynch

Both Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson and New York Federal Reserve President Timothy Geithner had pressured Bank of America to purchase Merrill Lynch. During the weekend of the Sept. 13, 2008, Bank of America auditors performed due diligence for a potential merger, and an agreement was publically announced on Sept. 15. At the beginning of December, information became known to Lewis that Merrill’s losses were going to be far worse than expected. The anticipated losses were in excess of $13 billion. Lewis asked advice from Bank of America’s legal staff and considered cancelling the offer to acquire Merrill Lynch. On Dec. 17, 2008, Ken Lewis met with Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke and Paulson; they both urged Lewis not to back out of the deal. They said that pulling out of the deal would create systemic risk to the U.S. economy. On Dec. 21, Lewis was also warned that the government would consider replacing the Board of Directors and management if Bank of America backed out of the deal. The officials also suggested that if Bank of America backed out then any further government assistance would be difficult to obtain. The idea behind this was to demonstrate to the market that even though Lehman had failed, the big banks of Wall Street were cooperating to keep the system running.

Over the next four weeks, the government and Bank of America negotiated a deal that included another $20 billion in direct aid. The government also agreed to back an additional $118 billion to cover potentially bad assets held by Merrill Lynch. None of the above-mentioned communications between the government and Lewis were conducted in an official manner. The government did not want public disclosure at the risk of creating systemic issues in the overall financial system. Lewis and the Board of Directors did not disclose the additional losses to the shareholders. According to Lewis, this decision was not his to make; instead, the government had directed Lewis to keep the information private.

Bonuses for Poor Performance

After the acquisition was finalized, without a public announcement, Bank of America allowed Merrill Lynch’s executives to distribute bonuses of approximately $3.6 billion before the deal closed. Perhaps indicating how these bank executives live in an elite bubble of their own making, neither Lewis nor Thain realized that this small amendment to the contract would eventually spark a state investigation. Oddly, Thain did not seem to understand it was wrong to pay bonuses out to poorly performing employees (whose actions led to the damaging losses), while accepting taxpayers’ money to bail out the bank.

At Bank of America’s request, most of the money would be paid out in cash before the deal closed. The early payment would actually reduce expenses for Bank of America in 2009, making it easier for the bank to hit its first-quarter numbers. Thain had also negotiated a new title for himself: President of Global Banking, Securities and Wealth Management. He would be responsible for planning and executing the merger of Merrill Lynch’s banking and trading business with that of Bank of America. With this deal, Merrill Lynch employees would emerge as winners, with thousands of Bank of America staffers laid off and replaced by their Merrill Lynch counterparts.

After word of the acquisition got out and the bonuses were paid, criticism focused on the price and potential risks, both of which were very high. Some argued that regardless of pressure from the U.S. government, Bank of America should have waited for the markets to adjust after the news of Lehman Brothers bankruptcy.

Ethical Issues:

As chairman and CEO of Bank of America, Lewis has a responsibility to inform the shareholders of the adverse conditions that were present in the Merrill Lynch merger. The same applies to CEO John Thain, who misled shareholders by not being transparent about the losses at Merrill Lynch and the bonuses paid. Another issue for both the CEOs is paying out bonuses right before the acquisition.

On the other hand, Lewis was also responsible for the overall wellbeing of the U.S. and global financial system. Another major crisis to the financial system would have had adverse impacts on Bank of America shareholders and customers. Millions of shareholders clearly had a major stake in the decisions facing Lewis. The CEO must also take into account the interests of nearly 200,000 employees and contractors.

Analysis of Ethical Issues:

The short-term consequences are more easily identified. Lewis and Thain had to consider that if the deal fell through, the overall economy would be adversely impacted. On the other hand, if the deal went through, the shareholders would take an economic blow in terms of diluted share value. Lewis estimated that it would take two to three years for the deal to bring economic value to the corporation, so any shareholders on a short-term horizon would suffer.

The long-term impacts are more difficult to predict. One could argue that letting Merrill Lynch fail would result in a total collapse; on the other hand, allowing the market to take its natural path would be in the best interest of the public and the shareholders.

Public disclosure of the bonuses paid and the true health of Merrill Lynch would have had an immediate impact on Lewis, the Board of Directors and both the companies. The government also stated that the Board of Directors and management would be forced out if the deal did not go through. This would have a large impact on the leaders. Lewis and the board members are all in financially secure positions; therefore, losing their jobs would not have a financial impact. But the corporation would suffer from a government-forced change in leadership with no financial help, not to mention if the deal did not go through and Merrill Lynch was declared bankrupt it would have created more panic in the market — and this was after the fall of Lehman Brothers. The real dilemma was deciding whether secrecy or disclosure would result in greater consequences.

Integrity:

“Doing the right thing” can easily be interpreted as disclosing the information to shareholders, but this action could also have a severe impact on the entire country. No matter what Lewis did, people would be impacted by the decision. Ken Lewis and Thain thought they had only two choices: continue with the deal and keep quiet or pull out of the deal and inform the shareholders of the material adverse conditions of the Merrill Lynch acquisition.

Moral Choices:

Ken Lewis faced enormous consequences without an easy way out. No matter what, Lewis would have to choose an action that would impact a large number of people. The best choice is likely the one that minimizes the damages. Lewis would have to make the choice for the greatest good.

Clearly, Lewis and Thain should not have given out the bonuses in light of the poor performance of management that resulted in the near collapse of Merrill Lynch. On this issue, Lewis and Thain acted unethically.

However, having done so, if Thain had disclosed the bonuses before the acquisition, all of his employees might have lost their jobs, as the deal would not have gone through. On the other hand, he also had to think about the shareholders, who would lose money, and the economy as a whole.

Utilitarian Analysis:

From the utilitarian philosophy of ethical decision making, we can break the decision down based on the choices that will have a greater impact. Failing to disclose the information would have a direct financial impact on the shareholders. Publically disclosing the materially adverse conditions would have potential impact upon the entire financial system. This risk would also impact Bank of America shareholders. Even though a lot of people would suffer from a utilitarian aspect, keeping silent appears to be the better choice.

Ethical decision making can also be based on the duties and obligations of the decision maker. In this case, Lewis and Thain have obligations to both the shareholders and the overall wellbeing of the U.S. financial system. Both Lewis and Thain also have a duty to consider the overall wellbeing and greater good of the entire country. This duty does not omit their obligation to the shareholders, but the universal appeal of the good of the community has a stronger pull than the individual shareholders of the corporation. Lewis’ and Thain’s reputations were on the line. Both were faced with failing at their primary responsibilities.

Ultimately, the decision should be based on seeking the greater good – or it might be more accurate to say choosing the lesser evil. Holding back the information would have certain consequences; however, we can draw a certain boundary around these consequences. Yes, the shareholders will be affected in the short term. However, the deal may turn out to be profitable in the long term. Disclosing the information is a much more dangerous choice. The damage would not only impact Bank of America and its shareholders, it could also easily create global effects.

In the best interest of the corporation, shareholders, and U.S. citizens, my thoughts are that although Ken Lewis and John Thain deceived their shareholders, they might have done the right thing for the greater good in the acquisition of Merrill Lynch without publicly disclosing material adverse consequences.

By: Pratik Patel

Editor: Angela Lutz

Works Cited

- Linda K. Trevino, Katherine A Nelson, “Managing Business Ethics”, (2010) Fifth Edition

- Jessica Silver-Greenberg & Susanne Craig, Bank of America Settle Suit Over Merrill for $2.43 Billion, September 2012

- Shareholders Transparency Demands Rise http://www.ethicsworld.org/corporategovernance/corporatereputation.php

- Greg Farrell and Henny Sender, ” The shaming of John Thain”, Financial Times, March 2009.

- Countrywide Financial Problems http://www.ehow.com/about_5444985_countrywide-financial-problems.html

- O.C. Ferrell, John Fraedrich, William Ferrell, “Business Ethics, Ethical Decision Making & Cases”, Ninth Edition

- Bank of America’s Merrill Scandal Reigniteshttp://www.cjr.org/the_audit/bank_of_americas_merrill_scand.php

- How the Thundering Herd Faltered and Fell http://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/09/business/09magic.html?pagewanted=all

Photo: Flickr by adibs