COP27: Adaptation Without Mitigation

By Corey O’Dwyer

Inability to balance climate change adaptation (the loss and damage fund) with climate change mitigation (ambitious fossil fuel policy) constitutes an ethical failure.

The 27th Conference of Parties (COP27) summit held in November of 2022, described by the United Nations (UN) as the “foremost global forum” for climate change discussion[1], had high expectations to deliver a ‘loss and damage’ fund, secure plans to phase out fossil fuels, and review climate finance pledges not kept[2]. Ultimately, COP27’s Sharm el-Sheikh Implementation Plan exceeded expectations in some areas but failed in others. The Plan exceeded expectations by finally establishing a loss and damage fund, ending what had been a decades-long fight by many climate-vulnerable countries for compensation from damages caused by climate disasters[3]. However, the fund came at the cost of implementing much-needed ambitious policy on fossil fuel reductions, with the final wording of the implementation plan only mentioning a need to transition to “low emissions”[4], thus achieving little in the way of combatting the root causes of climate change[5]. COP27’s failure to balance climate change adaptation (the loss and damage fund) with climate change mitigation (ambitious fossil fuel policy) constitutes an ethical failure. Investment into just one of these areas has “adverse effects”[6] on averting future climate disasters.

Loss and Damage Fund – COP27’s Biggest Success

Many consider COP27’s loss and damage fund a huge success for a multitude of reasons. Significantly, developed countries – the biggest emitters of greenhouse gasses – finally acknowledged their role in climate change, and its effects on developing and climate-vulnerable states. Second, the fund provides developing and climate-vulnerable states – primarily, from Africa, the Pacific and the Caribbean – the means to adapt to, prepare and mitigate the effects of climate disasters without taking on debt. Third, the loss and damage fund begins to remedy injustices whereby developing states suffer the consequences of actions to which they contributed negligible amounts.

Vanuatu first recommended a loss and damage fund at UN climate negotiations in 1991[7]. This idea has since been a point of contention between developing and developed states. The global north did not want to take responsibility for climate disasters, fearing the financial liability of such an admission. Conversely, developing states demanded developed states take responsibility and pay up, loathing the idea of fixing a problem they did not create. Yet, the latter shirked responsibility and accountability, despite G20 countries contributing to 75 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions[8]. A decades-long stalemate ensued. The stalemate saw only slight movement by the time of COP26, where it was agreed a three-year dialogue window would be opened to discuss the possibility of a loss and damage fund[9].

At the beginning of COP27, this stalemate seemed destined to endure, as developed states attempted to ‘stonewall’ loss and damage negotiation attempts – a decades old practice by the time of COP27[10]. US climate envoy John Kerry opposed the fund from the outset, and rejected suggestions high greenhouse-gas emitters should take responsibility for historic emissions[11]. That the loss and damage fund would be agreed upon only two-weeks later, was beyond belief for some experts like Nayanah Siva: “[I]f you had asked me a few months ago if this could be an outcome of COP27, I’d have said it was simply implausible.”[12] Yet already, US$300 million has been pledged by Europe[13], funds which will both compensate developing states for losses and damages incurred by climate change, and place more pressure on developed states to curb emissions[14]. The thirty-two-year long battle ended as developed nations take responsibility and accountability for their role in climate change, and provide compensation for losses and damages sustained from climate-related disasters. A stunning breakthrough for COP27, all considered.

For the countries of Africa, the Caribbean and Small Island Developing States (SIDS), the loss and damage fund represents a development from COP27, particularly given the climate disasters plaguing these regions over previous decades. The loss and damage fund marks a turning point in their ability to adapt, mitigate and prepare for future climate disasters, which are becoming increasingly frequent.

For Africa – a continent which only contributes to 3 per cent of global emissions[15] – the loss and damage fund can begin to subsidise the 1 per cent of GDP lost to climate disasters annually[16], and move funds spent on climate crises into industries like healthcare[17]. For the Caribbean, the fund can be used to eliminate the “significant debts” incurred by climate disasters[18] which cost around 2 per cent of annual GDP[19], while better preparing the region for future disasters – to which the Caribbean is “especially vulnerable.”[20] And, for SIDS countries, the fund means covering the costs of the ever-increasing number of floods and tropical storms which have cost trillions of dollars worldwide in the previous two decades[21], and the billions of dollars SIDS states specifically have lost to these climate-related disasters[22]. Whilst the loss and damage fund will not be a trillion dollar magic bullet that solves the myriad of climate-related crises these vulnerable regions face, the money goes a long way toward supporting and building resilience in these regions. Stemming the flow of cash lost by these developing states to climate catastrophes is a significant lifeline COP27 has provided, but this must be augmented, quickly, by ambitious mitigation policy, or the savings will be for naught.

Compensatory Justice

A perhaps underappreciated aspect of the loss and damage fund is its role in addressing the climate injustice and climate debt states owe to developing states. Labelled by UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres as “an important step towards justice,”[23] it is a clear attempt to right past wrongs. Compensatory justice is the phenomenon where actor ‘A’ is compensated by actor ‘B’ for harm suffered in the past by actor ‘B’[24]. Contextualised, this would be the “countries responsible for high carbon emissions […] [compensating] lower-income countries”[25]. The emissions gap and consequences gap between developed and developing states has been steep. The top 10 per cent of households with the highest per capita emissions contribute around 40 per cent of consumption-based household emissions, whilst the bottom 50 per cent contribute only around 15 per cent[26]. Yet, low-income households are the most vulnerable to climate disasters[27], and developing states are often situated in geographic regions most susceptible to life-altering climate disasters, like desertification or rising sea levels. Similarly, the G20 has contributed to no less than 67% of historical cumulative emissions, whilst least developed states have contributed only 0.5%[28]. The loss and damage fund, then, is a worthy step towards righting the scales of the climate injustice. The states which suffer most from emissions have contributed the least to global cumulative emissions[29], and seen almost none of the profits or benefits developed states have enjoyed from emissions-powered industries.

Figure 1: IPCC Working Group 3 Summary for Policymakers Report, page 10

Policy measures which provide compensatory justice have a respectable history of delivering positive outcomes in cases of environmental pollution, which are closely-related to climate change policies. The International Oil Pollution Compensation Funds (IOPC Funds) serve as a source of compensatory justice, providing member states with financial compensation for damages accrued by oil spills. The Fund has paid out around US$900 million to over 150 incidents since the Fund was established[30]. While this alone is impressive, the true success of the Fund lies in who it compensates, how it collects the money necessary to pay compensation, and how the Fund indirectly influences the oil industry to be better. All these achievements align with the objectives of the loss and damage fund, or are necessary additions to the loss and damage fund. The IOPC Funds pay compensation to anyone who has suffered from oil pollution, regardless of whether they are a fishing business from a remote village, a multinational corporation or a country’s government[31]. Take for instance, the sinking incident of oil tanker Solar 1 in 2006. 2000 tonnes of industrial oil spilt into the Guimaras Strait, resulting in US$2 million being paid to fisheries on Guimaras Island, farmers along the coast of the Philippines, government agencies, and a variety of cleaning contractors[32]. This example set by the IOPC Funds is one that many hope will be followed by COP27’s loss and damage fund. Previous climate disaster funds have failed to reach beyond the government level to provide for those who need the money the most – local communities[33].

The IOPC Funds generate the money necessary to pay compensation and influences the oil industry to do better, through taxation. The IOPC Funds gather compensation money from the source, imposing a levy on entities which receive 150,000 tonnes or more from oil transported overseas[34]. This not only is an intelligent way of gathering compensatory funds but is also an effective way of holding the oil industry accountable, which means the IOPC Funds can be a source of disaster mitigation as well as compensatory justice. The IOPC Funds have done a remarkable job of mitigating oil spill incidents. A UN study of oil pollution incidents since the 1970s found the IOPC Funds have greatly influenced the decline in oil spill disasters, attributing the reduction to the IOPC Funds to a “considerable extent”[35].

Experts and global leaders alike hope to see this form of funding in the loss and damage fund, with Guterres calling on developed countries to “tax the windfall profits of fossil fuel companies” so that funds are redirected “to countries suffering loss and damage.”[36] Such funding in the loss and damage fund would undoubtedly have positive outcomes in helping to mitigate further investment into fossil fuels, going beyond its original purpose as merely climate adaptation policy. If the IOPC Funds are anything to judge by, there is potential for good from the loss and damage fund. Climate change policy measures which provide compensatory justice have the capacity to function as both adaptation and mitigation when drafted ambitiously.

Weaknesses in the Loss and Damage Fund

While the loss and damage fund is COP27’s biggest success story, it comes with downsides and uncertainties. First, there are valid concerns the loss and damage fund could join the growing group of climate funds which are weak, conditional, or difficult to access, because COP27 did not outline specifically what the loss and damage fund would look like. Second, the loss and damage fund articulates a form of climate adaptation policy, meaning the fund addresses symptoms of climate change rather than causes of climate change, making the fund only as effective as climate mitigation policy. Third, COP27’s devotion to ratifying the loss and damage fund meant little progress was made in phasing out the use of fossil fuels, potentially dooming climate-vulnerable and developing states to being dependent on the loss and damage fund to survive.

The creation of a loss and damage fund brings about a variety of problems specific to this fund, while also facing other complications which have existed for years in other climate funds. Deciding what falls under the scope of climate loss and damage, and how much should be paid, is a difficult task. Things like infrastructure and housing are straightforward to pay for, but what of the destruction of cultural artefacts, indigenous cultural sites, ecosystems or the loss of life?[37] How are these irreplaceable artefacts and people quantified with money?

Then, there is the problem of how much money this fund has to begin with, and where it comes from. 76 developing countries have indicated they need around US$71 billion per year to adapt to climate change[38], yet developed countries have struggled to even make good on their COP15 pledge of US$100 billion per year to developing states[39], missing the mark by US$17 billion in 2020[40].

Similarly problematic, is where China fits in the loss and damage fund. China is classified by the UN as a developing country[41], making them eligible to apply for loss and damage funding, yet China is also the biggest net contributor to emissions in the world[42]. Is China then expected to contribute to the fund, or will China benefit from it? And finally, how will the funds from the loss and damage fund be paid out? Many climate funds – such as the Green Climate Fund and the Adaptation Fund – are problematic[43], as they give some funding out as loans, are difficult and slow to apply for, and often do not manage to support local communities[44]. In 2017-2018, half of the climate finance received by SIDS countries came in the form of “loans or non-grant mechanisms” which exacerbated debt struggles, lowered credit ratings and crippled borrowing capabilities in the event of future climate catastrophes[45]. If the loss and damage fund is to be successful, it needs to provide funds free of any strings attached, or the same problems arise. The loss and damage fund has the potential for good, or it could be disappointing. The transitional committee that COP27 charged with creating the loss and damage fund has to avoid the same pitfalls as previous climate funds, and must be generous and just in rulings on what constitutes loss and damage.

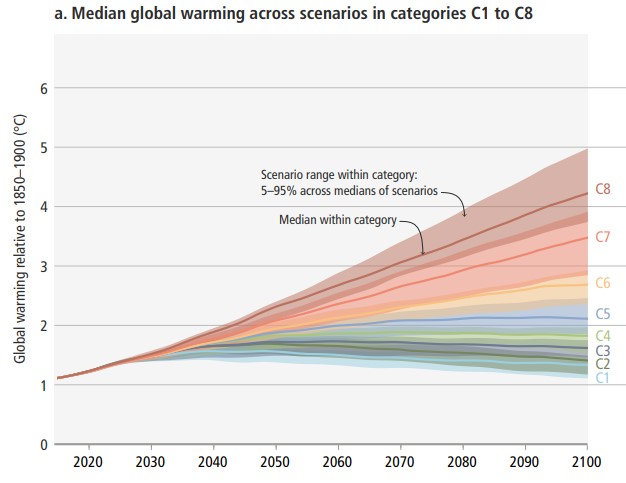

Figure 2: Median temperature increases in 8 different cases ranging from complete emissions elimination to no climate action (https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg3/)

Climate adaptation policy and climate mitigation policy are both equally important actions, as climate adaptation allows states to build resilience against current and future climate disasters, while climate mitigation works to prevent climate disasters from being as common or destructive. Due to the current state of global warming, both are needed in increasingly higher amounts, yet COP27 only saw major investment into climate adaptation, and little action on climate mitigation. The mitigation failure weakens the effectiveness of the loss and damage fund and means the most climate-vulnerable states will become increasingly reliant on the loss and damage fund as temperatures continue to rise. Going into COP27, the need for climate mitigation policy was dire. The United in Science 2022 Report found emissions reductions needed to be seven times higher to restrict warming to 1.5° Celsius[46]. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) concluded global warming would reach median levels of 3.2° Celsius by 2100 if mitigation policies are not strengthened[47]. Yet, the focus of COP27 ultimately was climate adaptation policy, as the loss and damage fund became the primary focus of the Summit. While a necessary and helpful fund, it risks becoming “a fund for the end of the world”[48] if the root cause of climate change – emissions – are not reduced[49]. Estimates indicate that 200 million people by 2050 could need humanitarian aid yearly due to climate disasters without further climate mitigation policy[50], undoubtedly beyond the scope any climate fund could hope to deal with. As such, the loss and damage fund is inherently weakened due to COP27 neglecting to pair the fund with ambitious and meaningful climate mitigation policy. COP28 must prioritise swift climate mitigation policy, for the equation is simple: “more fossil fuels means more loss and damage,”[51] and more loss and damage means climate-vulnerable states become reliant on funding to survive.

Figure 3: United in Science 2022 Report, page 18 (https://library.wmo.int/doc_num.php?explnum_id=11309)

Ethical Failings of COP27

The loss and damage fund addresses historic issues of climate injustice and climate debt owed by developed states to developing states, through the application of compensatory justice. In a vacuum the fund constitutes an excellent development, but given the dire climate context the world finds itself in, the policy is not enough. Indeed, despite agreement on a loss and damage fund, COP27 may be considered an ethical failure to countries most affected by climate disaster. UN Secretary-General Guterres highlighted this flaw in his closing speech at COP27, mentioning the “fund for loss and damage is essential – but it’s not an answer if the climate crisis washes a small island state off the map – or turns an entire African country to desert.” [52] COP27 needed to provide policy that achieved both compensatory justice and corrective justice, through climate adaptation policy and climate mitigation policy, respectively.

Climate mitigation policy is a form of corrective justice as it seeks to re-balance an injustice by correcting the current climate situation[53]. Contextualised, climate mitigation policy seeks to keep global warming from surpassing 1.5°Celsius so that climate-vulnerable states suffer less from the consequences of climate change. If COP27 had, for example, demanded countries pledge to create more ambitious Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) alongside the loss and development plan, it would have been an ethical success. In such a scenario, the world would be on track for warming under 2.5° Celsius by 2100[54], whilst also providing loss and damage support for countries which are suffering here and now. Instead, COP27 has neglected to fight for ambitious climate mitigation to go with its ambitious climate adaptation, risking a locking in of temperature rises beyond 2.5° Celsius, which will result in “further loss and damage due to climate impacts on people’s health and livelihoods.”[55]

COP27, therefore, has failed to provide corrective justice and more broadly, failed to maximise the overall good of humanity. It may not be long before the loss and damage fund is offset by more-frequent climate disasters, which will be partially fuelled by the summit’s failure to push climate mitigation policy. COP28 needs to right these ethical wrongs, for “what can’t be mitigated […] will be suffered,”[56] and the suffering of global warming will impact far more than just the global south in the not-so-distant future.

COP28 will have to make up for the shortcomings of COP27, with a concerted focus on climate change mitigation policy. COP28 must demand ambitious, radical and fast-tracked NDC’s, add more countries to the Just Energy Transition Partnerships, and revisit pledges to phase out the use of coal, gas, and oil as energy sources. Time is running out for emissions cuts to have the desired effects of limiting global warming to 1.5° Celsius, and thus limiting future losses and damages on scales never seen before. The loss and damage fund will also need to be a focus of COP28, to ensure it avoids the pitfalls of prior climate funds. COP27 was an historic summit, for both the right and wrong reasons: the summit that ended a thirty-year deadlock, and the summit which failed to further mitigate the causes of climate change.

Endnotes

[1] “What Are United Nations Climate Change Conferences?” Unfccc.int, United Nations, https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/what-are-united-nations-climate-change-conferences.

[2] “What to Expect at This Year’s UN Climate Conference: COP27.” UNEP, United Nations, 4 Nov. 2022, https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/what-expect-years-un-climate-conference-cop27.

[3] “What You Need to Know about the COP27 Loss and Damage Fund.” UNEP, United Nations, 29 Nov. 2022, https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/what-you-need-know-about-cop27-loss-and-damage-fund.

[4] “Decision CP.27 Sharm El-Sheikh Implementation Plan” Sharm El-Sheikh Implementation Plan, United Nations, 20 Nov. 2022, https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/cop27_auv_2_cover%2520decision.pdf.

[5] “COP27 – ‘Loss and Damage’ Success Tempered by Lack of Implementation – United Nations Environment – Finance Initiative.” UN Enviroment Programme, United Nations, 7 Dec. 2022, https://www.unepfi.org/themes/climate-change/cop27-loss-and-damage-success-tempered-by-lack-of-implementation/.

[6] Ezzeldin, Khaled and Dan Adshead. United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative, 2022, Adapting to a New Climate, https://www.unepfi.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Adapting-to-a-New-Climate.pdf. Accessed 6 Mar. 2023.

[7] Rowling, Megan. “COP27 Will Be a ‘Failure’ without New Climate Damage Fund, Says Vanuatu.” Reuters, 16 Nov. 2022, https://www.reuters.com/business/cop/cop27-will-be-failure-without-new-climate-damage-fund-says-vanuatu-2022-11-15/. Accessed 7 Mar. 2023.

[8] Lamb, William F., and Giacomo Grassi. United Nations Environment Programme, 2022, Emissions Gap Report 2022, https://www.unep.org/resources/emissions-gap-report-2022. Accessed 5 Mar. 2023.

[9] Rowling, Megan. “COP27 Will Be a ‘Failure’ without New Climate Damage Fund, Says Vanuatu.” Reuters, 16 Nov. 2022, https://www.reuters.com/business/cop/cop27-will-be-failure-without-new-climate-damage-fund-says-vanuatu-2022-11-15/. Accessed 7 Mar. 2023.

[10] Alayza, Natalia, et al. “COP27: Key Takeaways and What’s Next.” World Resources Institute, 8 Dec. 2022, https://www.wri.org/insights/cop27-key-outcomes-un-climate-talks-sharm-el-sheikh. Accessed 5 Mar. 2023.

[11] Masood, Ehsan, et al. “COP27 Climate Talks: What Succeeded, What Failed and What’s Next.” Nature, vol. 612, no. 7938, 21 Nov. 2022, pp. 16–17., https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-03807-0.

[12] Siva, Nayanah. “COP27: A ‘Collective Failure.’” The Lancet, vol. 400, no. 10366, 26 Nov. 2022, p. 1835., https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(22)02407-2.

[13] Kurukulasuriya, Pradeep, et al. “What the New ‘Loss and Damage’ Fund Needs for Success.” United Nations Development Programme, United Nations, 22 Nov. 2022, https://www.undp.org/blog/what-new-loss-and-damage-fund-needs-success. Accessed 6 Mar. 2023.

[14] “COP27 – ‘Loss and Damage’ Success Tempered by Lack of Implementation.” UN Environment Programme Finance Initiative, 7 Dec. 2022, https://www.unepfi.org/themes/climate-change/cop27-loss-and-damage-success-tempered-by-lack-of-implementation/. Accessed 6 Mar. 2023.

[15] Siva, Nayanah. “COP27: A ‘Collective Failure.’” The Lancet, vol. 400, no. 10366, 26 Nov. 2022, p. 1835., https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(22)02407-2.

[16] Ezzeldin, Khaled and Dan Adshead. United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative, 2022, Adapting to a New Climate, https://www.unepfi.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Adapting-to-a-New-Climate.pdf. Accessed 7 Mar. 2023.

[17] “What You Need to Know about the COP27 Loss and Damage Fund.” UNEP, United Nations, 29 Nov. 2022, https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/what-you-need-know-about-cop27-loss-and-damage-fund.

[18] Ezzeldin , Khaled, and Dan Adshead. UN Environment Programme Finance Initiative, 2022, Adapting to a New Climate, https://www.unepfi.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Adapting-to-a-New-Climate.pdf. Accessed 7 Mar. 2023.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] World Wildlife Fund, 2022, Options for Strengthening Action on the Ocean and Coasts under the UNFCCC, https://wwfint.awsassets.panda.org/downloads/unfccc_ocean_climate_options_3_june_2022.pdf. Accessed 5 Mar. 2023.

[22] “Less Division, More Ambition: High-Level Dialogue on Loss and Damage in Small Island Developing States.” United Nations Office of the High Representative for the Least Developed Countries, United Nations, 8 Nov. 2022, https://www.un.org/ohrlls/events/less-division-more-ambition-high-level-dialogue-loss-and-damage-small-island-developing.

[23] Kurukulasuriya, Pradeep, et al. “What the New ‘Loss and Damage’ Fund Needs for Success.” United Nations Development Programme, United Nations, 22 Nov. 2022, https://www.undp.org/blog/what-new-loss-and-damage-fund-needs-success. Accessed 6 Mar. 2023.

[24] “Financial Crisis 2008, Perpetrators, and Justice.” Seven Pillars Institute for Global Finance and Ethics, 23 May 2013, https://sevenpillarsinstitute.org/financial-crises-perpetrators-and-justice/.

[25] Siva, Nayanah. “COP27: A ‘Collective Failure.’” The Lancet, vol. 400, no. 10366, 26 Nov. 2022, p. 1835., https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(22)02407-2.

[26] Portner, H. O., et al. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2022, Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change [Summary for Policymakers], https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg3/. Accessed 2 Mar. 2022.

[27] International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, 2019, The Cost of Doing Nothing: The Humanitarian Price of Climate Change and How It Can Be Avoided, https://www.ifrc.org/sites/default/files/2021-07/2019-IFRC-CODN-EN.pdf. Accessed 6 Mar. 2023.

[28] Lamb, William F., and Giacomo Grassi. United Nations Environment Programme, 2022, Emissions Gap Report 2022, https://www.unep.org/resources/emissions-gap-report-2022. Accessed 5 Mar. 2023.

[29] Zielinski, Chris. “COP27 Climate Change Conference: Urgent Action Needed for Africa and the World.” Thorax, vol. 78, no. 3, 18 Oct. 2022, pp. 217–218., https://doi.org/10.1136/thorax-2022-219740. Accessed 6 Mar. 2023.

[30] “Funds Overview.” IOPC Funds, https://iopcfunds.org/about-us/.

[31] “Compensation and Claims Management.” IOPC Funds, https://iopcfunds.org/compensation/.

[32] “Incident Map: Solar 1.” IOPC Funds, Oct. 2022, https://iopcfunds.org/incidents/incident-map#1918-11-August-2006.

[33] Wyns, Arthur. “COP27 Establishes Loss and Damage Fund to Respond to Human Cost of Climate Change.” The Lancet Planetary Health, vol. 7, no. 1, 8 Dec. 2022, pp. 21–22., https://doi.org/10.1016/s2542-5196(22)00331-x. Accessed 7 Mar. 2023.

[34] IOPC Funds, 2020, Report to UN Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea, https://www.un.org/depts/los/general_assembly/contributions_2020/IOPCFunds.pdf. Accessed 22 Mar. 2023.

[35] United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 2012, Liability and Compensation for Ship-Source Oil Pollution: An Overview of the International Legal Framework for Oil Pollution Damage from Tankers, https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/dtltlb20114_en.pdf. Accessed 22 Mar. 2023.

[36] “‘Polluters Must Pay’: UN Chief Calls for Windfall Tax on Fossil Fuel Companies.” The Guardian, 21 Sept. 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/sep/20/un-secretary-general-tax-fossil-fuel-companies-climate-crisis. Accessed 22 Mar. 2023.

[37] Kurukulasuriya, Pradeep, et al. “What the New ‘Loss and Damage’ Fund Needs for Success.” United Nations Development Programme, United Nations, 22 Nov. 2022, https://www.undp.org/blog/what-new-loss-and-damage-fund-needs-success. Accessed 6 Mar. 2023.

[38] Watkiss, Paul, et al. United Nations Environment Programme, 2022, Adaptation Gap Report 2022, https://www.unep.org/resources/adaptation-gap-report-2022. Accessed 5 Mar. 2023.

[39] “Climate Finance and the USD 100 Billion Goal.” OECD, https://www.oecd.org/climate-change/finance-usd-100-billion-goal/.

[40] “What You Need to Know about the COP27 Loss and Damage Fund.” UNEP, United Nations, 29 Nov. 2022, https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/what-you-need-know-about-cop27-loss-and-damage-fund.

[41] Abnett, Kate. “Explainer: COP27: What Is ‘Loss and Damage’ Funding, and Who Should Pay?” Reuters, 20 Nov. 2022, https://www.reuters.com/business/cop/cop27-what-is-loss-damage-compensation-who-should-pay-2022-11-06/. Accessed 8 Mar. 2023.

[42] Lamb, William F., and Giacomo Grassi. United Nations Environment Programme, 2022, Emissions Gap Report 2022, https://www.unep.org/resources/emissions-gap-report-2022. Accessed 5 Mar. 2023.

[43] “COP27 Reaches Breakthrough Agreement on New ‘Loss and Damage’ Fund for Vulnerable Countries.” United Nations Climate Change, United Nations, 20 Nov. 2022, https://unfccc.int/news/cop27-reaches-breakthrough-agreement-on-new-loss-and-damage-fund-for-vulnerable-countries. Accessed 27 Feb. 2023.

[44] Wyns, Arthur. “COP27 Establishes Loss and Damage Fund to Respond to Human Cost of Climate Change.” The Lancet Planetary Health, vol. 7, no. 1, 8 Dec. 2022, pp. 21–22., https://doi.org/10.1016/s2542-5196(22)00331-x. Accessed 7 Mar. 2023.

[45] “Less Division, More Ambition: High-Level Dialogue on Loss and Damage in Small Island Developing States | Office of the High Representative for the Least Developed Countries, Landlocked Developing Countries and Small Island Developing States.” United Nations Office of the High Representative for the Least Developed Countries, United Nations, 8 Nov. 2022, https://www.un.org/ohrlls/events/less-division-more-ambition-high-level-dialogue-loss-and-damage-small-island-developing.

[46] Canadell, Josep G., et al. World Meteorological Organisation, 2022, United in Science 2022, https://library.wmo.int/doc_num.php?explnum_id=11309. Accessed 7 Mar. 2023.

[47] Portner, H. O., et al. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2022, Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change [Summary for Policymakers], https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg3/. Accessed 2 Mar. 2022.

[48] “Loss and Damage Fund Risks Becoming ‘Fund for the End of the World’.” WWF, World Wildlife Fund, 20 Nov. 2022, https://wwf.panda.org/wwf_news/press_releases/?6982966%2FWWF-Loss-and-damage-fund-risks-becoming-fund-for-the-end-of-the-world-due-to-COP27-failures.

[49] “What You Need to Know about the COP27 Loss and Damage Fund.” UNEP, United Nations, 29 Nov. 2022, https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/what-you-need-know-about-cop27-loss-and-damage-fund.

[50] International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, 2019, The Cost of Doing Nothing: The Humanitarian Price of Climate Change and How It Can Be Avoided, https://www.ifrc.org/sites/default/files/2021-07/2019-IFRC-CODN-EN.pdf. Accessed 6 Mar. 2023.

[51] Masood, Ehsan, et al. “COP27 Climate Talks: What Succeeded, What Failed and What’s Next.” Nature, vol. 612, no. 7938, 21 Nov. 2022, pp. 16–17., https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-03807-0.

[52] Guterres, Antonio. “António Guterres (Secretary-General) on the Closing of COP27 | UN Web TV.” United Nations, United Nations, 19 Nov. 2022, https://media.un.org/en/asset/k12/k12p31t118.

[53] “Financial Crisis 2008, Perpetrators, and Justice.” Seven Pillars Institute for Global Finance and Ethics, 23 May 2013, https://sevenpillarsinstitute.org/financial-crises-perpetrators-and-justice/.

[54] “Government Ministers at COP27 Call for More Ambitious Climate Action .” UNFCCC, United Nations, 15 Nov. 2022, https://unfccc.int/news/government-ministers-at-cop27-call-for-more-ambitious-climate-action.

[55] Siva, Nayanah. “COP27: A ‘Collective Failure.’” The Lancet, vol. 400, no. 10366, 26 Nov. 2022, p. 1835., https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(22)02407-2.

[56] Wyns, Arthur. “COP27 Establishes Loss and Damage Fund to Respond to Human Cost of Climate Change.” The Lancet Planetary Health, vol. 7, no. 1, 8 Dec. 2022, pp. 21–22., https://doi.org/10.1016/s2542-5196(22)00331-x. Accessed 7 Mar. 2023.