ESG Investing: Perils and Pertinence

By Elizabeth Si Jie Ng

The Great Hypocrisy: When Sanctimony Becomes Scandal

On 31 May 2022, 50 German police officers stormed the premises of Deutsche Bank and its asset management subsidiary DWS. It marked a turning point in Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) history as it was the first time an asset manager was raided in a probe into allegations of greenwashing. According to a whistle-blower, DWS had overstated its use of ESG criteria in its investments. [1] What ensued was an industry-wide reckoning that brought scandals to light. Less than two months later, HSBC’s Global Head of Responsible Investment resigned after facing a backlash for downplaying climate risks. [2] By the end of the year, the US Securities and Exchange Commission doubled down on its ESG greenwashing crackdown, imposing unprecedented penalties on BNY Mellon and Goldman Sachs for misleading customers over their ESG investments. [3]

For ESG proponents, this litany of woes was a rude awakening: ESG has morphed into mere window dressing for the kind of socially irresponsible investing it was designed to replace. Meanwhile, it confirmed the worst suspicions of ESG detractors: virtue-signalling – or “woke” capitalism – has no place in investment. [4] As the controversy over ESG continues to brew, the elephant in the room remains: is this the beginning of the end for ESG?

The Core of ESG Investing: What It Entails

ESG is broadly defined as the set of environmental, social, and governance issues factored into the analysis, selection, and management of investments. [5] In theory, ESG investing comprises an analytical tool for evaluating a company’s performance in Environmental standards, Social responsibility, and ethical Governance (Figure 1). [6] In practice, it is a metrics used by investors to select institutions and corporations for asset allocation, to generate long-term, sustainable financial returns. [7] To manage their portfolio, investors continually monitor the material risks and opportunities posed by ESG factors. [8]

Figure 1: Examples of ESG Factors

Source: ESG Investing and Government Regulation, Seven Pillars Institute

Conceived in the wake of notorious scandals such as Exxon Valdez’s oil spill and Enron’s chicanery, ESG was founded on a scintilla of idealism. [9] First mooted in the 2004 Who Cares Wins report, the idea was endorsed by 23 financial institutions collectively representing more than US$6 trillion in assets. The report envisioned that “a better consideration of ESG would ultimately contribute to stronger and more resilient investment markets, as well as contribute to the sustainable development of societies”. [10] This belief that principles and profits were symbiotic was later reaffirmed in the 2006 United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment (UNPRI), a framework established under the auspices of the UN Global Impact and UN Environment Programme Finance Initiative. Yet, even under the guise of interdependency, these policy agendas tacitly acknowledged the relationship between moralistic social value and financial materiality was never equal – the former was framed as a means for the latter. ESG investing is primarily aimed at limiting exposure to ESG-related risk factors and boosting risk-adjusted returns; its concern with sustainability is subsidiary. This begs the question: which of the two masters should investors serve when both become diametrically opposed?

The 2 ‘R’s of ESG: Less Risks, More Returns

For ESG advocates, financial and social value are merely two sides of the same coin, in no way dichotomous. Put simply, if a business is unprofitable, it is unsustainable; if a business is unsustainable, it is unprofitable. By promoting the culture of doing well by doing good, ESG investing cultivates sustainable value that will last for both markets and societies. There are two key mechanisms through which such sustainable value can be created: lowering risks and increasing returns. [11]

Firstly, ESG ratings involve an assessment of financial materiality, which measures the relevance of particular ESG factors to corporations’ financial performance. [12] Empowered with such disclosure, investors identify and avoid risks more effectively. Consequently, corporations are motivated to mitigate potential ESG-related risks, as risk-averse investors reward those who fare better in ESG ratings. For example, to boost their ESG performance and appeal to investors, companies may implement strategies on renewable energy to alleviate the impact of climate change on business operations. Such a corporate shift is socially beneficial. Empirical evidence also supports this: integrating ESG criteria into investment processes bolsters portfolio diversification and reduces portfolio risks. Stocks with higher ESG ratings have lower total and unsystematic risks than stocks with similar systematic risks but poorer ESG ratings.[13] In part, companies with inferior ESG performance have more exposure to long-term disaster and reputational risks. [14] There is a robust negative relationship between stocks’ ESG ratings and volatility, with higher ESG ratings being correlated with lower stock volatility. This relationship presents itself as even more prominent during periods of market volatility, especially in social or economic crises such as the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. [15] In fact, ESG funds appear to be more resilient during down markets. In 2022, the broad Morningstar US Sustainability Index fell by 18.9%, outperforming the 19.4% decline in the S&P 500. [16] The inclusion of ESG in investing therefore optimises risk management, while fostering socially responsible corporate behaviour. [17]

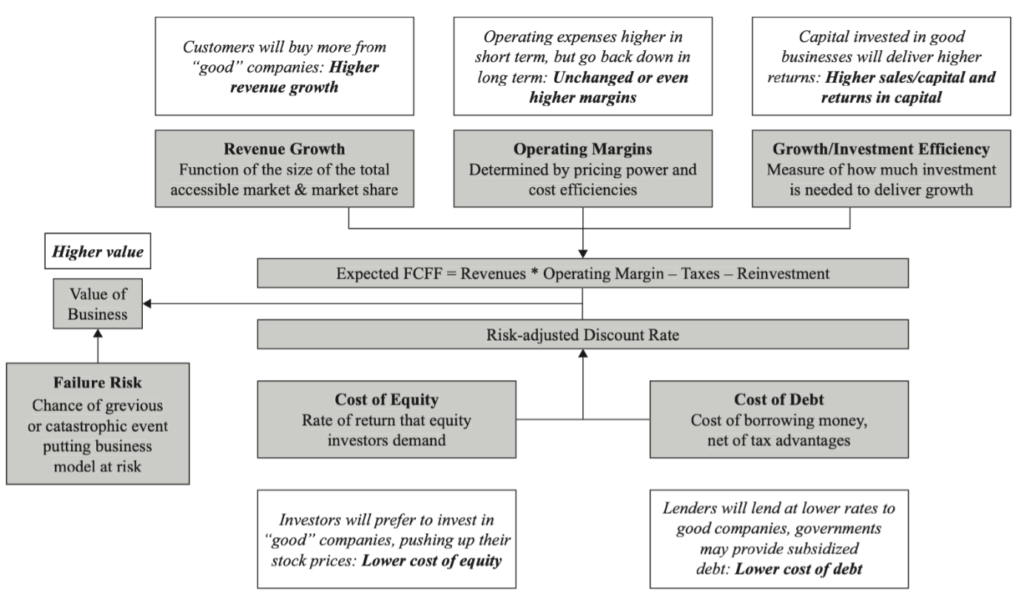

Secondly, with ESG reporting, investors can calibrate their investment decisions according to firms’ ESG performance. They are likely to allocate more assets to companies on the winning side of ESG-driven growth trends, which proffer attractive investment opportunities. Conversely, they divest from companies with lower ESG standards, since their negative spill over effects on wider society shape the very non-financial factors that could undermine their bottom line. [18] For example, heavy emitters do not merely harm the environment, they are more vulnerable to legal penalties (e.g., carbon taxes) which result in significant market value losses. [19] Meanwhile, companies at the forefront of developing low-carbon products are well-positioned to ride on the wave of green subsidies (e.g., the US Inflation Reduction Act and EU Green Deal Industrial Plan) and environmental consumerism. This lowers their costs of capital – in terms of debt and equity – and enables them to capture greater market share. Empirically, from 2016 to 2020, the returns of 74% of sustainable funds ranked in the top 50% of their Morningstar category. [20] A study by Morgan Stanley Institute for Sustainable Investment finds that at the height of the pandemic in 2020, sustainable equity funds outperformed non-ESG peer funds by a median total return of 4.3% while sustainable taxable bond funds surpassed their peers by a median total return of 0.9%. [21] Overall, since profit-driven companies are motivated to align with investors’ ESG preferences, ESG investing sets in motion a reinforcing virtuous cycle of superior risk-adjusted returns and positive social impacts (Figure 2). [22]

Figure 2: Benefits of ESG in terms of Higher Expected Free Cash Flow to Firm (FCFF) and Lower Risks

Source: Valuing ESG: Doing Good or Sounding Good? NYU Stern School of Business

Positive Ethics of ESG Investing: The Common Good

In his book Theory of Justice, John Rawls defines the common good as “certain general conditions that are…equally to everyone’s advantage”. [23] This approach to ethics regards individuals as part of a larger community. The theory assumes individuals’ own good links inextricably to the good of their community. Community members are thus bounded by the pursuit of mutual and shared benefits.

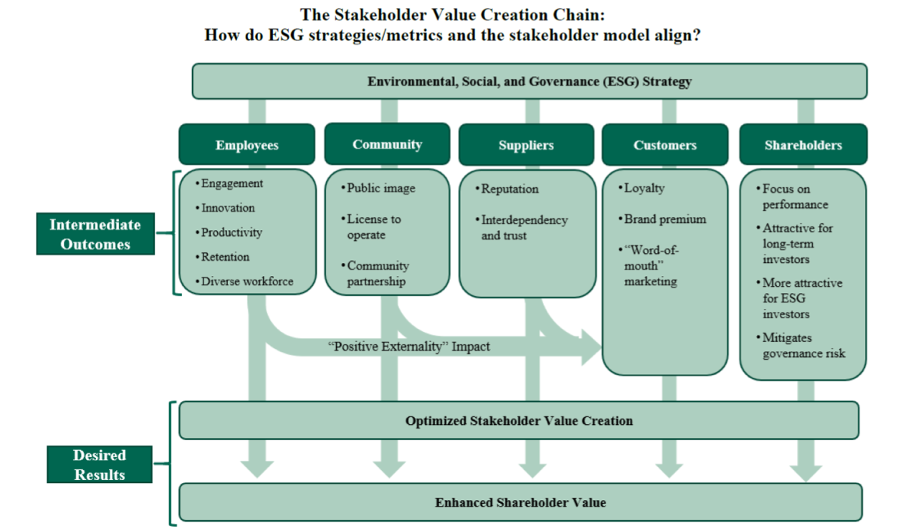

ESG investing mirrors this concept, as it shifts from the narrow shareholder model to the broader stakeholder model. [24]It rejects shareholder primacy highlighted in Milton Friedman’s The Social Responsibility of Business Is To Increase Its Profits, which propounds the sole mandate of corporations is to maximise shareholder profits.[25] Instead, ESG investing embraces stakeholder governance, aimed at long-term, sustainable value creation for the wider community. In the international fora, there is emerging consensus that corporate governance should be a synergistic collaboration between corporations, shareholder investors, and other community stakeholders to achieve socio-economic prosperity. The likes of the World Economic Forum’s The New Paradigm and Davos Manifesto, published in 2016 and 2020 respectively, demonstrate society has awakened to the dangers of forcing short-term value enhancements without regard for the long-term value of the common good. [26] On the corporate front, prominent financial market players have expressed similar sentiments. This attitudinal shift culminated in a letter by the CEO of BlackRock Larry Fink to other CEOs in 2022, where he argued, “it is through effective stakeholder capitalism that capital is efficiently allocated, companies achieve durable profitability, and value is created and sustained over the long-term.”[27] The Stakeholder Value Creation Chain further illustrates the interplay between ESG strategy, enhanced shareholder value, and optimised stakeholder value creation (Figure 3). [28] The burgeoning appeal of stakeholder primacy within ESG investing reflects its ethical pursuit of the common good.

Figure 3: The Stakeholder Value Creation Chain

Source: The Stakeholder Model and ESG, Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance

Practical Flaws: Falling Short in Both Financial and Social Returns

Critiques of ESG investing are hardly without merit. In theory, it can reap a panoply of benefits. Yet in reality, ESG investing is hamstrung by various practical implementation challenges that vitiate its ability to yield real financial and social returns.

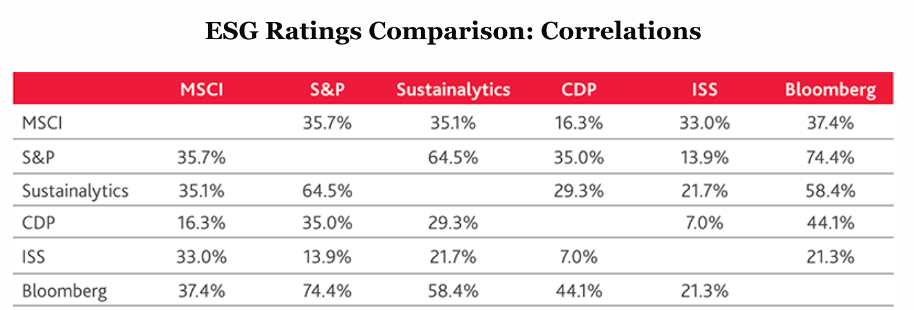

Firstly, there is limited comparability between ESG ratings across major providers, which apply varying methodologies to the same set of data. Central to this divergence is the confusion over what factors ESG ratings should measure. To some, ESG is supposed to assess the impact companies have on the welfare of their stakeholders. Companies can improve their ESG ratings by engaging in socially desirable activities or withdrawing from harmful ones. To others, including the MSCI, ESG is designed to evaluate the impact of ESG risk factors on the company. Increasing ESG ratings will require mitigating financially material risk factors. [29] Given such discrepancies in the components of ESG analysis, there could be different ratings for the same company. As a result, investors’ decisions may not be consistent with companies’ true risks and returns. In terms of overall ESG ratings, the correlations across key providers lie on a wide spectrum from 0.14 (between ISS and S&P Global) to 0.65 (between S&P Global and Sustainalytics) (Figure 4). [30] Meanwhile, assessments of individual E, S, and G subcomponents also differ greatly, as evidenced by the correlations of only 0.11, 0.18 and -0.02 respectively between MSCI and Sustainlytics. [31] The implications of this issue are manifold. On one hand, it raises doubts about how accurate the positive correlation between ESG index and profitability is; on the other hand, it lends credence to contrasting evidence that suggest the aforementioned correlation is at best tenuous and at worst unfounded.

Figure 4: Correlations between ESG Ratings in 2021

Source: ESG Ratings: Navigating Through the Haze, CFA Institute

Secondly, the dearth of transparency in the criteria, methodology, and threshold values used by ESG providers also casts a shadow on whether ESG really benefits society. For example, without proper disclosure of how green bonds are issued, corporations can easily engage in greenwashing. An investigation by the European Commission discovered 42% of green claims were exaggerated, false, or deceptive, indicating greenwashing happens on an industrial scale. [32]

Ethical Flaws: When the Ends are Incompatible with the Means

Herein lies the nub of the controversy: the ends of ESG investing are out of step with its means. It expects non-financial factors to deliver on financial returns, which may distort the very nature of those non-financial considerations. Looking at socio-economic issues with a profit-tinted lens is not just futile, it also is ethically unsound. As spotlighted in The Ethics of ESG Investing, ESG funds reward ethical behaviour but do not perceive such behaviour as inherently valuable.[33]Their main objective is to leverage principles (which can only be judged on a philosophical basis) to accrue profits (which is ascertained through investment calculations). This contravenes Immanuel Kant’s moral law, which argues that a human action is only morally good if it is done from a sense of duty. The duty must be a formal principle based not on self-interest or from a consideration of what results might follow. [34]

The Missing ‘E’ in ESG: The Ethics of the Principal-Agent Problem

The principal-agent relationship is an arrangement in which one entity appoints another to act on its behalf. [35] In the case of investing, the investor is the principal, while the financial executives or portfolio managers are the agents. In theory, the agent should have no conflict of interest in carrying out an act on behalf of the principal. In reality, agents may have several incentives to pursue their own agenda, even at the expense of the principal. Although accountable to the latter, the agent can take advantage of various asymmetries – for example in execution, information, time, or fee structure. ESG investing creates another axis of asymmetry, encouraging managers to pursue their own interests rather than those of their investors. [36]

Firstly, the criteria for ESG investing are not clearly defined, proffering room for agents (managers and executives) to impose their own agenda on their principals (investment customers and clients). Applying ESG principles often require highly contextualised value judgments, due to inevitable trade-offs between environmental, social, and governance considerations. Crucially, not everything that is socially desirable is good for the environment; not everything that is environmentally friendly positively impacts a firm’s governance.

The unequal principal-agent relationship is fuelled by the fact there is no singular methodology for measuring ESG performance. Different service providers and indices rank the same firms differently. For example, under FTSE’s environmental rating, electric-car maker Tesla received the lowest possible score. Under the MSCI, Tesla scored nearly the highest. [37] Such arbitrariness also exists within individual indices. The FTSE ranked Tesla low because of the large electricity consumption of its cars and supply chain. However, FTSE did not seem to apply the same criterion to Alphabet, the parent company of Google, a service that is dependent on electricity on both ends of its supply chain. These outcomes are particularly problematic because fund managers have neither the mandate to exercise value judgments on the behalf of their clients nor the superior expertise to make better value judgments.

Moreover, within most agency relationships, optimal contracting is a pivotal issue. Contracts give agents an incentive to optimise performance. However, agents are also concerned about their own reputation. While the performance is shared with the principal, the reputation belongs to the agent. With ESG, agents can burnish their personal reputation while charging their principals for it. In most contracts, the principal pays for expenses related to accessing data and gaining knowledge for ESG. This process can either happen directly or through the agents who would increase management fees, independent of performance. If investors are simply attracted to the ESG label but have no real ability or time to make sense of the myriad ratings, managers can package and sell ESG funds as an attractive product, which is more lucrative than conventional funds due to the higher fee structure. In 2022, Harvard Business Review reported ESG funds typically charge fees 40% higher than traditional funds. [38] Conforming to ESG also provides misguided justifications for underperformance. In the name of ESG, agents could change indices or modify tracking errors. Therefore, ESG investing side-lines the ethical obligations agents owe to principals.

Conflict over Fiduciary Duty: The Question of Liability

The system of ESG investing is underpinned by the concept of fiduciary duty, which states that the person given authority to act on behalf of others, must act in the best interest and in the manner of the person they are representing. [39]However, how this duty is applied depends on jurisdictional regulations as to whom a fiduciary duty is owed.

In examining the fiduciary duty of corporate directors, interested parties are divided into two categories: shareholders and stakeholders. While shareholders are parties who own a direct share of the investment, stakeholders are parties who do not have an ownership interest in a company but have an interest in the actions of the company. The definition of a stakeholder varies by jurisdiction, but can include employees, customers, suppliers, the community, and the government. In a jurisdiction which adopts stakeholder theory, directors owe a fiduciary duty to the shareholders, but may consider the interests of the stakeholders. In a jurisdiction which adopts shareholder primacy, fiduciary duty and considerations are limited to those of the shareholders. In most cases, European countries, where ESG finds its origins, are stakeholder jurisdictions. Meanwhile, the US is a shareholder jurisdiction. [40]

Similarly, the fiduciary duty of fund managers is owed to the beneficiaries or investors – that is, those who own a direct interest in the fund. Unlike corporate directors, there is no separate stakeholder category. The limits of their fiduciary duty is thus determined by the rules of the game. Some jurisdictions operate under a sole interest rule, where the only consideration for fund managers is the financial interests of the beneficiaries. Other jurisdictions afford flexibility under the prudent person’s rule. It stipulates that investors must ensure the quality, liquidity, security, and profitability of their portfolio as a whole, thus allowing considerations of non-financial factors in parallel with financial factors. [41]

In jurisdictions where fiduciary duty is extended only to shareholders, justifying a trade-off of profits for ESG priorities becomes less viable. Meanwhile, for fund managers in jurisdictions where they can consider non-financial factors alongside financial factors, there is room for incorporating ESG into investing. However, in jurisdictions where the sole interest rule applies, ESG investing may be a breach of fiduciary duty, if it is merely motivated by asset managers’ own sense of ethics or desire to obtain collateral benefits for third parties.

In 2015, UNPRI, UN Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI), UNEP Inquiry and UN Global Compact released a publication, Fiduciary Duty in the 21st Century, in which they acknowledged that ESG was problematic under shareholder or sole interest fiduciary standards. [42] When factoring the financial returns of ESG products, ESG investing also appears to be a breach of fiduciary duty. A 2019 University of Chicago study of 20,000 mutual funds discovered that none of the high sustainability funds outperformed any of the lowest rated funds.[43] Managers who leave underperforming ESG investments in their portfolio, or add new underperforming ESG investments, may thus be breaching fiduciary duty. As such, without any distinct legal definitions or regulatory standards in reporting, corporate directors and fund managers are placed in the precarious position where ESG investing is a breach of fiduciary duty, leaving them liable to civil action. Nevertheless, while ESG is not a part of fiduciary duty, it may be considered if two factors are met: firstly, the investor reasonably concludes that ESG investing will benefit the beneficiary directly by improving risk-adjusted returns; and secondly, the investor’s exclusive motive for ESG investing is to obtain this direct benefit. [44]

Reinventing ESG: A New Hope for the Future

Undeniably, ESG investing is caught in an identity crisis. What it truly stands for continues to rest on murky grounds, as the tug-of-war between shareholders and stakeholders; profits and principles; principals and agents rage on. Yet, to throw the baby out with the bathwater would only give destructive capitalism a free rein. Rather than side-line ESG investing, we need to redesign its purpose and functions.

Firstly, ESG should be streamlined. Amalgamating a labyrinth of environmental, social, and governance objectives is self-defeating as it forces businesses and investors to make trade-offs between the three to boost their performance. Instead, sustainable investing should be narrowed down to a specific goal and measurement that can be uniformly applied. Since the standards for social and governance practices vary depending on the nature of the industry, it is more efficient to focus on the environment, which can be easily measured by a single metric: emissions. Put simply, ESG should be narrowed to ‘E’, which should represent emissions and not all environmental factors. The more standardised the ‘E’ rating is, the easier it would be to hold large carbon culprits accountable. [45]

Fundamentally, ESG investing should not be touted as a silver bullet for encouraging sustainability. Doing good does not necessarily translate to doing well; doing well is often inimical to doing good. In fact, if businesses are willing to withstand the stigma, it is often much more profitable to externalise costs, such as pollution, onto society rather than bear them directly. Ultimately, it falls on governments to reconcile goals of profit and welfare maximisation. Regulators must enact policies that make ESG practices superior in terms of financial performance, since companies are primarily concerned with materiality. For example, investing in water-saving technology is not deemed as a financially material ESG practice in a context where water tariffs are too low to justify the investment. However, it can become financially material once regulators raise tariffs to appropriate levels. As such, ESG investing should be shaped as a supplementary tool to policies that enforce punitive action on harmful business practices (e.g., higher carbon taxes or regulations of minimum standards) or those that promote valuable business operations (e.g., green subsidies). It should not displace or divert attention away from government policies, which are key to shaping the financial viability of existing corporate strategies. The vision of a sustainable future must start with governments taking the helm, and directing investors and businesses to channel capital into socially valuable activities. For ESG investing, the options are brutally clear: to restructure or relegate into obscurity.

Endnotes

[1] Walker, Owen and Miller, Joe. “German police raid DWS and Deutsche Bank over greenwashing allegations.” The Financial Times, 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/ff27167d-5339-47b8-a261-6f25e1534942 (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[2] Walker, Owen. “HSBC banker quits over climate change furore.” The Financial Times, 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/5ff24114-5777-4d00-a014-ad36ce948d64 (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[3] Franklin, Joshua and Temple-West, Patrick. “Goldman Sachs to pay $4mn penalty over ESG fund claims.” The Financial Times, 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/0e2b6e41-4113-437f-824b-80d7acd29579 (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[4] Pollman, Elizabeth. “The Making and Meaning of ESG.” ECGI Working Paper Series in Law, 2022, https://www.ecgi.global/sites/default/files/working_papers/documents/esgcoverecgifinal.pdf (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[5] Inderst, Georg and Stewart, Fiona. “Incorporating Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Factors into Fixed Income Investment.” World Bank Group, 2018, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/c9a16bb1-aea2-5124-804f-bcf4621d1835/content (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[6] Stanley, Daniel. “ESG Investing and Government Regulation.” Seven Pillars Institute, 2018, https://sevenpillarsinstitute.org/esg-investing-and-government-regulation/ (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[7] Boffo, Riccardo and Patalano, Robert. “ESG Investing: Practices, Progress and Challenges.”, OECD Paris, 2020, https://www.oecd.org/finance/ESG-Investing-Practices-Progress-and-Challenges.pdf (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[8] Demine, Vladimir and Borhaug, Marte. “The Material Risk Indicator: A proprietary framework for assessing ESG risks and opportunities.” Morgan Stanley Insights, 2021, https://www.morganstanley.com/im/en-us/individual-investor/insights/articles/the-material-risk-indicator-a-proprietary-framework-for-assessing-esg-risks-and-opportunities.html (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[9] Agnew, Harriet et al. “How ESG investing came to a reckoning.” The Financial Times, 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/5ec1dfcf-eea3-42af-aea2-19d739ef8a55 (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[10] United Nations. “The Global Compact. Who Cares Wins: Connecting the Financial Markets to a Changing World?” United Nations, 2004, https://www.unglobalcompact.org/docs/issues_doc/Financial_markets/who_cares_who_wins.pdf (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[11] Bannier, Christina, E. et al. “Doing Safe by Doing Good: Risk and Return of ESG Investing in the US and Europe.” Centre for Financial Studies, 2019, https://www.uni-giessen.de/de/fbz/fb02/fb/professuren/bwl/bannier/dateien/190619ESGPaper.pdf (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[12] Emerick, Dean. “What is Materiality in ESG?” ESG The Report, https://www.esgthereport.com/what-is-materiality-in-esg/ (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[13] Hoepner, Andreas G.F. “Portfolio Diversification and Environmental, Social or Governance Criteria: Must Responsible Investments Really Be Poorly Diversified?” SSRN Electric Journal, 2010, https://www.tias.edu/docs/default-source/documentlibrary_fsinsight/paper-portfolio-diversification-and-esg-criteria.pdf (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[14] Cornell, Bradford and Damodaran, Aswath. “Valuing ESG: Doing Good or Sounding Good?” The Journal of Impact and ESG Investing, 2020, https://www.classactionconference.com/uploads/1/1/8/7/118726463/valuing_esg_with_damodaran_-_published_version_1.pdf (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[15] De, Indrani and Clayman, Michelle, R. “The Benefits of Socially Responsible Investing: An Active Manager’s Perspective.” Journal of Investing, 2015, vol, 24, no. 4, 49–72.

[16] Norton, Leslie. “ESG Investing Keeps Pace with Conventional Investing in 2022.” Morningstar Sustainable Investing, 2023, https://www.morningstar.com/sustainable-investing/esg-investing-keeps-pace-with-conventional-investing-2022 (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[17] EDHEC-RISK Climate Impact Institute. “Does ESG Investing Improve Risk-Adjusted Performance.” EDHEC Business School, 2023, https://climateimpact.edhec.edu/does-esg-investing-improve-risk-adjusted-performance (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[18] Taylor, Lucian A. et al. “Sustainable investing in equilibrium.” Journal of Financial Economics, 2021, vol. 142, no. 2, 550–571.

[19] Karpoff, Jonathan M. et al. “The Reputational Penalties for Environmental Violations: Empirical evidence.” Journal of Law and Economics, 2005, vol. 68, 653–675.

[20] US SIF: The Sustainable Investment Forum. “Financial Performance with Sustainable Investing.” US SIF, 2023, https://www.ussif.org/performance (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[21] Morgan Stanley Institute for Sustainable Investment. “Sustainable Funds Outperformed Peers in 2020 During Coronavirus.” Morgan Stanley, 2021, https://www.morganstanley.com/ideas/esg-funds-outperform-peers-coronavirus (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[22] Cornell, Bradford and Damodaran, Aswath. “Valuing ESG: Doing Good or Sounding Good?” NYU Stern School of Business, 2020, https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3557432 (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[23] Hussain, Waheed. “The Common Good.” The Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy, 2018, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/common-good/ (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[24] Schoenmaker, Dirk. Investing for the Common Good: A Sustainable Finance Framework. Bruegel Essay and Lecture Series, 2017.

[25] Friedman, Milton. “A Friedman Doctrine – The Social Responsibility of Business Is To Increase Its Profits.” The New York Times, 1970, https://www.nytimes.com/1970/09/13/archives/a-friedman-doctrine-the-social-responsibility-of-business-is-to.html (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[26] Lipton, Martin et al. “Understanding the Role of ESG and Stakeholder Governance Within the Framework of Fiduciary Duties.” Harvard Law School, 2022, https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2022/11/29/understanding-the-role-of-esg-and-stakeholder-governance-within-the-framework-of-fiduciary-duties/ (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[27] Fink, Larry. “Larry Fink’s 2022 Letter To CEOs: The Power of Capitalism.” BlackRock, 2022, https://www.blackrock.com/dk/intermediaries/2022-larry-fink-ceo-letter (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[28] Martin, Blaine et al. “The Stakeholder Model and ESG.” Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance, 2020, https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2020/09/14/the-stakeholder-model-and-esg/ (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[29] Larcker, David F. et al. “ESG Ratings: A Compass Without Direction.” Stanford Closer Look Series, 2022, https://ssrn.com/abstract=4179647 (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[30] Prall, Kevin. “ESG Ratings: Navigating Through the Haze.” CFA Institute, 2021, https://blogs.cfainstitute.org/investor/2021/08/10/esg-ratings-navigating-through-the-haze/ (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[31] Dimson, Elroy et al. “Divergent ESG Ratings.” The Journal of Portfolio Management, 2020, vol. 47, no. 1, 75–87.

[32] European Commission. “Screening of websites for ‘greenwashing’: half of green claims lack evidence.” European Commission Press Releases, 2021, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_21_269 (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[33] Seven Pillars Institute. “The Ethics of ESG Investing.” YouTube, 16 October 2020, https://youtu.be/OdkdrQX1wg0 (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[34] Kant, Immanuel. The moral law: Kant’s groundwork of the metaphysic of morals. New York: Routledge, 1953. Edited by Paton, H. J.

[35] Schneider, Henrique. “Scenarios for investment managers’ exploitation of ESG.” GIS Sustainability, 2020, https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/esg/ (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[36] Fang, Lily. “Will ESG Investing Solve Our Pressing Problems?” INSEAD Knowledge, 2023, https://knowledge.insead.edu/economics-finance/will-esg-investing-solve-our-pressing-problems (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[37] Mormann, Felix and Mormann Milica. “It’s Time to Give Companies Standalone Climate Ratings.” Harvard Business Review, 2022, https://hbr.org/2022/05/its-time-to-give-companies-standalone-climate-ratings (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[38] Pucker, Kenneth P. and King, Andrew. “ESG Investing Isn’t Designed to Save the Planet.” Harvard Business Review, 2022, https://hbr.org/2022/08/esg-investing-isnt-designed-to-save-the-planet (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[39] Martindale, Will et al. “ESG Risks and Opportunities: A Fiduciary Duty Perspective.” In Making the Financial System Sustainable. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

[40] McGowan, Jonathan, A. “The Trouble with Tibble: Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Fiduciary Duty.” The University of Chicago Business Law Review, 2020, https://businesslawreview.uchicago.edu/online-archive/trouble-tibble-environmental-social-and-governance-esg-and-fiduciary-duty (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[41] Federal Financial Supervisory Authority. “Prudent Person Principle.” Federal Financial Supervisory Authority, 2020, https://www.bafin.de/EN/Aufsicht/VersichererPensionsfonds/Kapitalanlagen/PrudentPersonPrinciple/prudent_person_principle_node_en.html (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[42] Sullivan, Rory et al. “Fiduciary Duty in the 21st Century.” UNPRI, UNEP FI, UNEP Inquiry and UN Global Compact, 2015, https://www.unepfi.org/fileadmin/documents/fiduciary_duty_21st_century.pdf (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[43] Bhagat, Sanjai. “An Inconvenient Truth About ESG Investing.” Harvard Business Review, 2022, https://hbr.org/2022/03/an-inconvenient-truth-about-esg-investing (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[44] McGowan, Jonathan, A. “The Trouble with Tibble: Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Fiduciary Duty.” The University of Chicago Business Law Review, 2020, https://businesslawreview.uchicago.edu/online-archive/trouble-tibble-environmental-social-and-governance-esg-and-fiduciary-duty (Accessed 29 July 2023).

[45] The Economist. “ESG should be boiled down to one simple measure: emissions.” The Economist, 2022, https://www.economist.com/leaders/2022/07/21/esg-should-be-boiled-down-to-one-simple-measure-emissions (Accessed 29 July 2023).