EU Carbon Border Tax: Justice Matters

By Elizabeth Si Jie Ng

The First of Its Kind: The European Union (EU) Carbon Border Tax Levy

The EU has discovered how to police carbon emissions beyond its borders. In July 2021, the group proposed a levy officially designated as the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM).[1] CBAM is part of the EU’s “Fit for 55” policy package, which aims to reduce net greenhouse gas emissions 55% below 1990 levels by 2030. This is a milestone target for achieving climate neutrality by 2050, as set forth in the 2019 European Green Deal. [2]

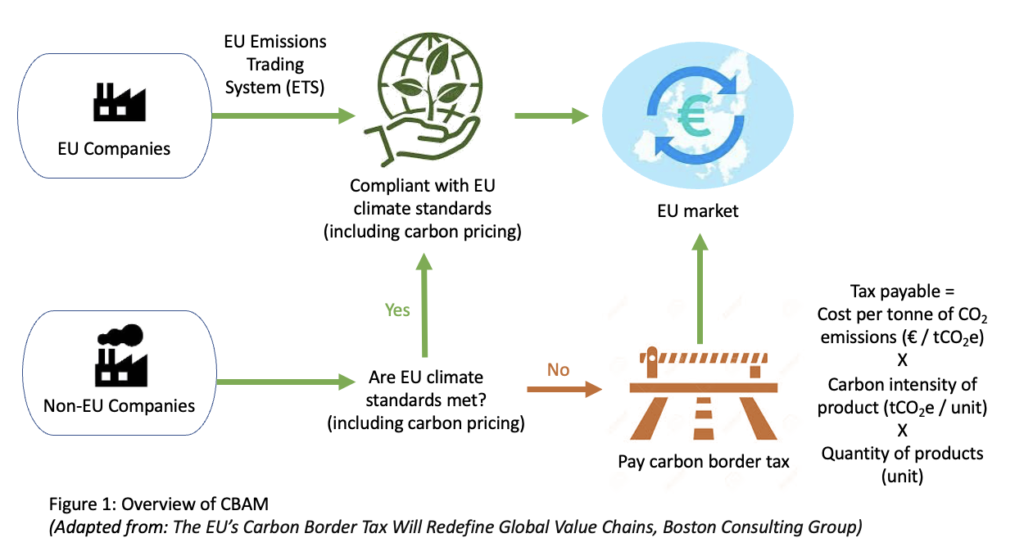

CBAM works as an import tariff for carbon-intensive goods entering the EU from third countries, which don’t tax carbon at an EU-approved level. [3] It requires importers to pay a carbon price at the border by purchasing certificates covering the scope of embedded emissions in their imports – which is the amount of direct (Scope 1) and indirect (Scope 2) emissions. [4] The cost of these certificates corresponds to the carbon price faced by EU domestic producers under the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) (Figure 1). [5]

The EU ETS is a cap-and-trade system. It limits the amount of emissions (‘cap’) by treating emission allowances as a commodity to be traded (‘trade’). It requires domestic producers in certain carbon-intensive sectors to acquire enough allowances to cover their emissions through auctions. [6] In the absence of a universal, harmonised carbon pricing policy, this creates a disparity in incentives for climate mitigation between the EU and its trading partners. Pegging CBAM to the average trading price of EU ETS allowances therefore, ensures the regulatory costs borne by domestically produced products also apply to similar, but otherwise unregulated, imports from countries with lower environmental standards than the EU. [7]

Playing the Long Game: The Purpose of CBAM

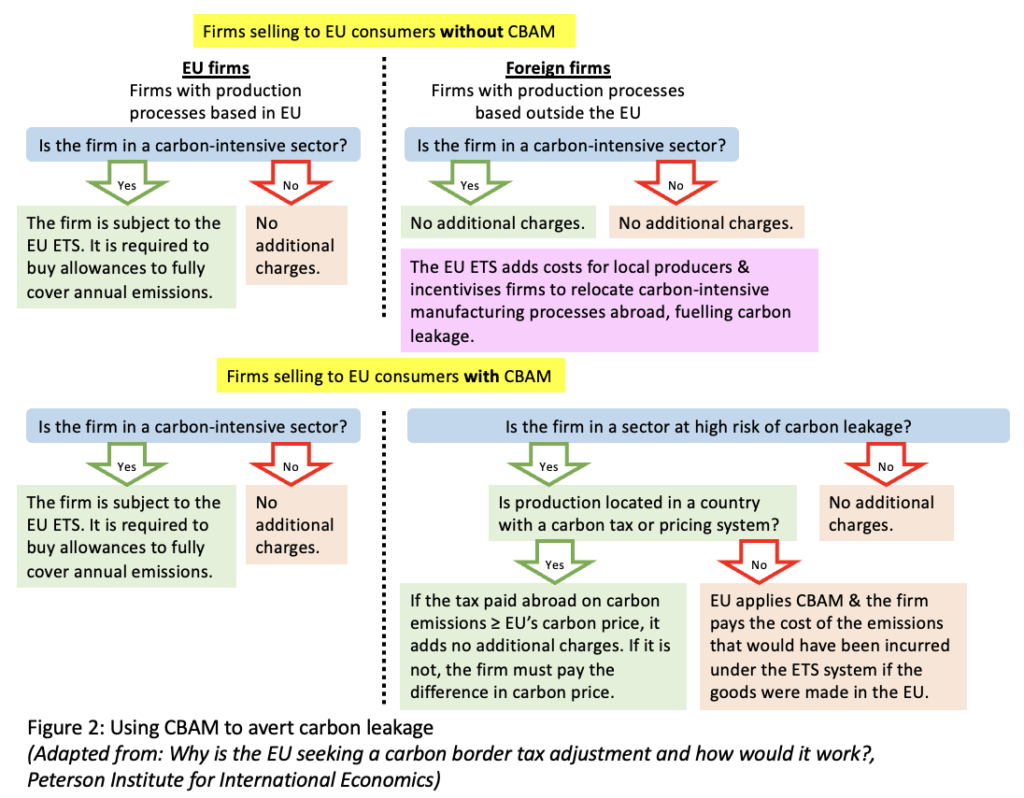

By increasing the price of energy inputs within the EU, the EU ETS encourages carbon leakage, when production relocates to countries with less stringent carbon emissions legislation, or when cheaper carbon-intensive imports replace EU products.[8] This imbalance affects competition, income and energy. In terms of competition, increased cost of production within the EU undermines firms’ competitiveness, inducing them to shift to jurisdictions without carbon pricing. Consequently creating distortions in the relative prices of domestic and foreign goods, terms of trade, and thus global distribution of income, fuelling economic inefficiency. Due to lower demand for fossil fuels in the EU, the price of high-emission energy in the global market may decrease. This increases its demand and hence emissions in unregulated jurisdictions.[9] As a result, EU ETS is self-defeating as overall emissions may not decline and could even increase. CBAM attempts to ameliorate the above issues by taxing foreign production. On one hand, it disincentivises dirty production from shifting to less heavily taxed jurisdictions, reducing the risks of carbon leakage. [10] On the other hand, it levels the playing field between European manufacturers and foreign competitors, allowing the former to maintain their competitiveness (Figure 2).[11]

The Action Plan: CBAM’s Implementation

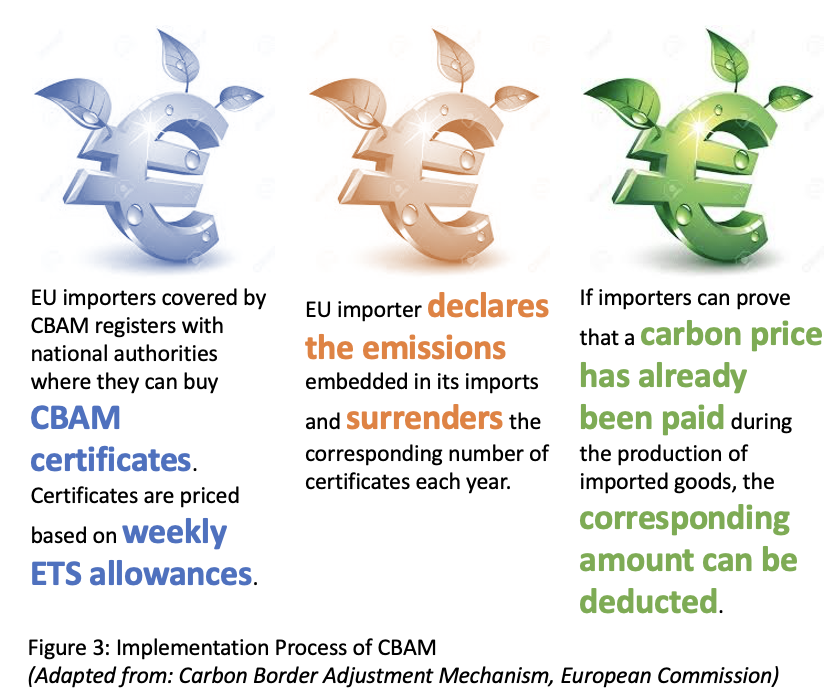

CBAM will initially apply to the main carbon-intensive goods and precursors: aluminium, cement, electricity, fertilisers, hydrogen, iron, and steel. All non-EU countries will be affected by it, except those participating in the EU ETS (including Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway) or those with emission trading systems linked to the EU ETS (Switzerland). [12] EU importers are required to purchase CBAM permits comparable to the carbon price that would have been paid, had they been operating under the EU ETS. To avoid double taxation, CBAM certificates can be reduced to account for carbon prices already paid in the country of origin (Figure 3). [13]

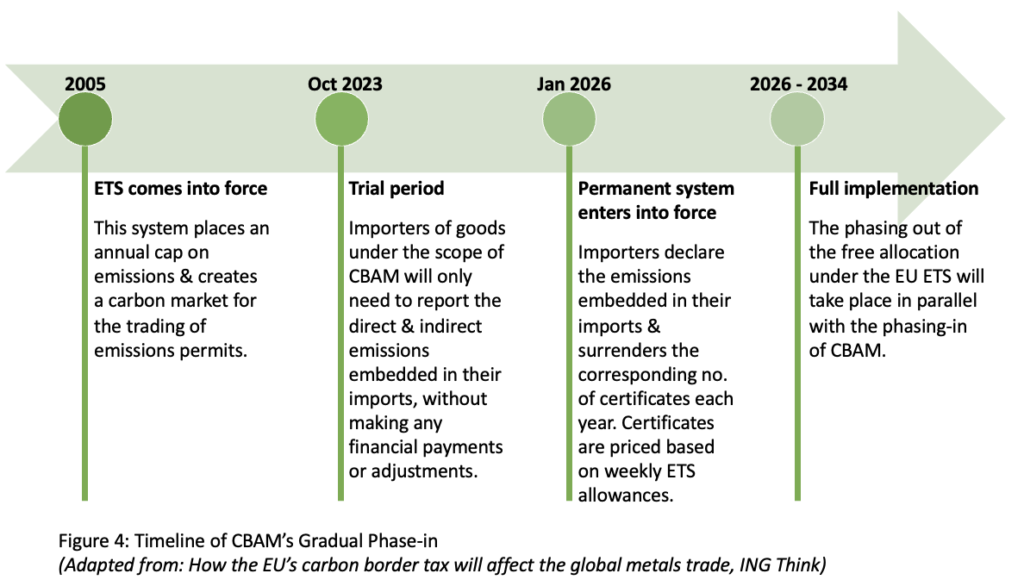

During a three-year transitional phase commencing 1 October 2023, affected importers are only required to fulfil reporting obligations. From 2026, importers must declare yearly the quantity of embedded emissions in their products in the preceding year, and surrender the corresponding number of CBAM certificates (Figure 4). [14] This progressive phase-in plan concurrently ceases the free allocation of EU ETS allowances for emissions-intensive and trade-exposed (EITE) industries.[15] As such, during the transition period, CBAM only applies to the proportion of emissions not subjected to free allowances under the EU ETS. By 2035, CBAM will be in full force while all free allowances will be completely phased out. A fully implemented CBAM will eventually capture more than 50% of the emissions in ETS-covered sectors.[16]

Basis for Ethical Analysis: The Two Faces of CBAM

To appraise the morality of CBAM, we must consider the dual-function of border adjustment mechanisms. In theory, to correct the competitive disadvantage faced by domestic industries under the EU ETS, CBAM should simultaneously implement an import charge and export rebate.[17] The former levels the playing field for goods consumed within the EU, while the latter levels the playing field for products exported to overseas markets where local producers are not penalised for emissions. These considerations allow for equivalence in carbon pricing across countries, provided the carbon border levy mirrors the EU’s internal carbon tax and is imposed alongside export rebates – that is, refund for allowances purchased by EU exporters in ETS sectors. Under these conditions, both domestic and foreign producers would bear the same carbon price within the EU and abroad. [18] However, in practice, the EU has yet to introduce export rebates, for fear they would breach World Trade Organisation’s (WTO) rules by favouring exporters. The WTO may classify export rebates as a type of prohibited export subsidy under the WTO Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures. [19] To circumvent this legal risk, the EU chose to retain a gradually declining share of free ETS allowances for some exporters. Nevertheless, this only serves as a temporary and partial solution to the challenge of export-related carbon leakage. [20] Hence, the following principles will analyse the ethics of levying import taxes without commensurate export rebates.

Harm-Avoidance Justice: Method of Least Harm

Harm-avoidance justice focuses on the rights of future generations, and the ethical obligation to effectively prevent avoidable harm in order to safeguard their well-being.[21] It is an outcome-oriented principle that prioritises efficiency over equity in assigning climate responsibility. [22] Given the devastating severity of climate change, its potential existential threat and long-term damage on humanity collectively, harm-avoidance justice assumes the cumulative effects of climate mitigation are more critical than its impacts on individual countries. The theory therefore, demands a utilitarian cost-benefit analysis to determine the strategy that would overall avert the most harm. Consequently, CBAM is only defensible if it reduces global emissions. However, this must be complemented with considerations of CBAM’s socio-economic effects on human well-being. If CBAM creates greater welfare losses than the predicted effects of climate change, there are little grounds for CBAM according to harm-avoidance justice. It is hence necessary to evaluate two empirical realities: the policy effectiveness of CBAM in mitigating emissions, and the extent of welfare losses inflicted by CBAM vis-à-vis the climate devastation that it can possibly forestall. [23]

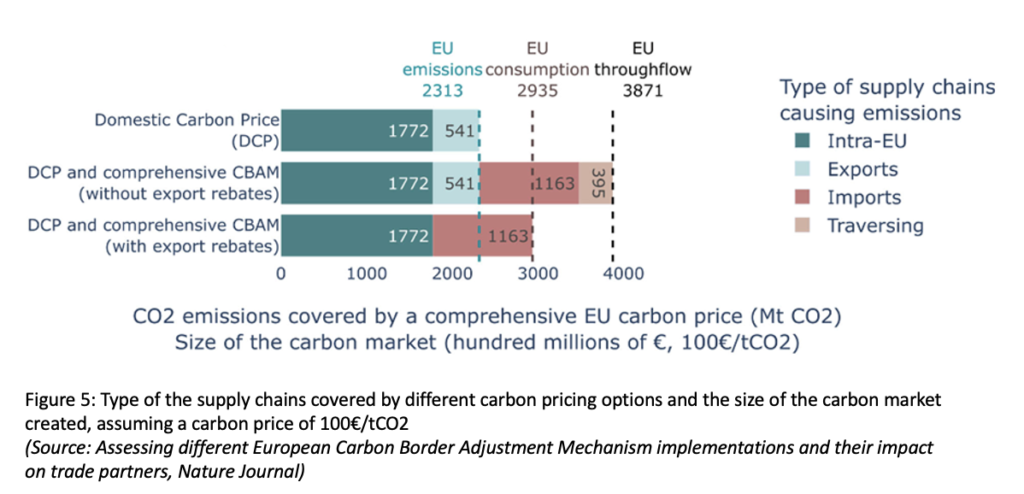

Nonetheless, comparing the short-term welfare costs of CBAM to the long-term benefits of emission reductions requires datasets that may not currently exist, given the subjectivity of discount rates and uncertainties inherent in climate modelling. Crucially, calculations of whether CBAM can reduce emissions and by how much remain contentious. Although the European Commission estimates that CBAM will decrease carbon leakage in six carbon-intensive sectors by 29% by 2030, it is inadequate to only account for the change in carbon leakage. [24] Reducing production-based carbon leakage does not necessarily result in carbon efficiency, as it could concomitantly engender consumption-based carbon leakage and perverse supply chain effects. [25] Firstly, without export rebates, the price signal of the EU ETS is channelled downstream to non-EU consumers. EU exports are thus less price competitive, causing them to lose market share in foreign markets. They are likely to be substituted by more emission-intensive goods imported from third countries. Since EU products are, on average, less carbon-intensive, this could lead to an overall increase in emissions (Figure 5). [26] Secondly, CBAM applies to raw materials used for local production but not to end products with higher carbon footprint. This creates incentives to import cheaper, carbon-intensive finished articles rather than producing the same goods domestically with taxable inputs. This further undermines European manufacturing, which often emits less carbon and creates value. [27]

At the same time, the lure of retaining access to the world’s largest trading bloc could galvanise other countries to price emissions, which is critical for cutting global emissions. [28] CBAM also places an upstream pressure on firms and their input suppliers to green their production processes, since reducing emissions would relieve the cost burden of import tariffs and boost competitiveness. These evince that CBAM could reduce emissions, though the extent would depend on empirical evidence.

Beyond empirical analysis, this theory also hinges on the type of ethical framework used to weigh policy outcomes – prioritarianism or sufficientarianism. Prioritarianism gives priority to improving the well-being of the worse-off over that of the well-off. CBAM’s impacts on the least well-off therefore, hold more weight within aggregate estimates. [29] Meanwhile, sufficientarianism is concerned with individuals securing enough goods. If CBAM deprives some individuals of the bare minimum, it is ethically untenable even if its overall effects are beneficial. [30] This is reflected in the Greenhouse Development Rights, which require countries to consider the global distribution of income. Countries with income below a ‘development threshold’ should be guaranteed a minimum income that secures their ‘right to development’. This could suggest exempting countries below the threshold from the costs of CBAM, in order to minimise total welfare losses. [31]

Burden-Sharing Justice: Determining Who Should Pay More

Burden-sharing justice seeks the most equitable way of distributing duties so that each party bears a fair portion of the costs. [32] This concept includes three key principles:

- The Polluter Pays Principle (PPP) dictates that agents who are responsible for climate change should bear the full costs of its abatement. [33]

- The Ability to Pay Principle (ATP) holds that agents with higher capacity to pay should contribute a larger share to ameliorating climate change. [34]

- The Beneficiary Pay Principle (BPP) posits that benefits arising from a higher emissions record should be either surrendered or compensated for. Thus, the greater the benefits received from climate change, the larger the amount owed in terms of climate action.

Burden-sharing justice is formally enshrined in the 2015 Paris Agreement, under the clause of Nationally Determined Contributions. It reflects the tenet of “common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities, in the light of different national circumstances” (CBDRRC).

Polluter Pays Principle (PPP)

CBAM is designed to make carbon-intensive industries pay. This is intuitively aligned with the PPP as it disincentivises high-carbon imports, reducing the market shares of highly polluting producers. However, there are several plausible counter-arguments against such justification. Firstly, CBAM neglects the historical implications of the PPP.[35] Based on data from 1751 to 2017, the former EU-28 is historically responsible for 22% of global cumulative emissions. [36] CBAM forces several developing countries to contribute proportionately more than what they ought to, since they have cumulatively lower emissions than the EU. Approximately $16 billion-worth of exports from developing countries to the EU could face additional charges. [37] Secondly, a CBAM compatible with WTO rules inevitably transgresses PPP. There is an underlying tension between international trade law, which is driven by efficiency considerations, and international environmental law (PPP), which is concerned with equity. [38] Moreover, not all causes of climate change can be attributed to human action. Natural processes, such as volcanic eruptions and solar variations, can also affect the Earth’s climate. [39] In such cases, there is no polluter who should pay. In light of such limitations, a more viable PPP would consider that countries should bear their share of measurable climate burden, so long as doing so does not push them beneath a decent standard of living or contravene the agreed rules of WTO.

Ability to Pay Principle (ATP)

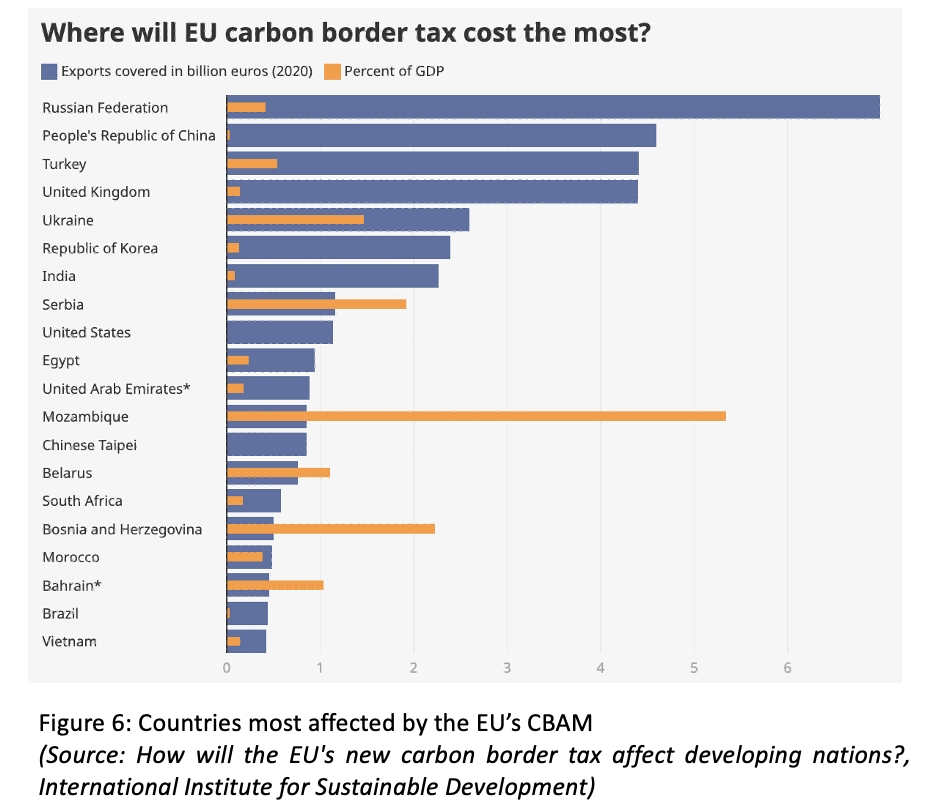

Under ATP, the costs of climate mitigation and adaption should be met by the wealthiest. [40] However, estimations of wealth based on aggregate GDP or the proportion of GDP needed for climate action fail to discriminate between economic wealth and correlated well-being. A 1% drop in GDP in emerging economies could create unacceptable levels of hardship, unlike advanced economies that experience fewer repercussions. Instead, the ability assessed in ATP should be based on the overall well-being or capability of society, with additional weight given to the least well-off who are more likely to see their capabilities diminished by CBAM. [41] The most affected tend to be non-diversified countries concentrated in Africa, whose primary exports to the EU belong to carbon-intensive industries. [42] These countries are also least likely to have carbon pricing or the administrative capacity to comply with declarations of their production’s carbon intensity. They would therefore, pay higher CBAM rates, at least initially. CBAM thus appears to be inimical to ATP.

Beneficiary Pays Principle (BPP)

BPP defends the notion that involuntary beneficiaries of high emissions possess remedial obligations of corrective justice to others. The difference between BPP and PPP is BPP acknowledges countries are not morally culpable for their emissions due to imperfect information. [43] It is therefore, unfair to hold them liable for the full costs of their actions or bear duties in proportion to their emission records. Instead, excusably ignorant countries should surrender the value of the benefits they derived from burning larger amounts of fossil fuels. This suggests countries in the Global North must contribute more since past industrial processes increased their standard of living. BPP also extends to the present failures to curb emissions, which allow polluting countries to maintain their high-emissions dependent lifestyles. Additionally, BPP applies to the context of deploying climate policies, which indicates that countries which involuntarily benefit from high-risk climate policies such as geoengineering, should compensate others for their benefits. However, a more appropriate moral standpoint would be first concerned with the effects of climate change on victims, rather than the benefits accrued by the perpetrators – since the latter is made problematic only in relation to their harmful effects on another party. [44] The BPP is thus more relevant only when the duties of high-emitting countries to CBAM cannot be performed, or when the harm caused by climate change cannot be attributed to a specific country.

Legal Issues of World Trade Organisation (WTO) Compatibility

With its focus on imports, CBAM is bound by the rules of the WTO, in particular the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). The GATT stipulates equal trading opportunities and non-discrimination requirements. [45] This creates a design dilemma for the EU, should it incorporate differential treatment (CBDRRC) under the CBAM. While GATT prohibits charges on imports in excess of states’ tariff schedules and absolute quantitative restrictions, it does not definitively preclude internal fiscal measures or regulations. [46] This could refer to the application of a domestic measure to ‘like’ imported products, even if it is formally applied at the border. However, this ploy is contentious. Firstly, it is unclear whether CBAM qualifies as ‘internal’. For this, the ‘obligation to pay’ a charge must ‘accrue due to an internal event, such as the distribution, sale, use or transportation of the imported product’. As the requirement to surrender CBAM certificates is linked to importation, the measure may not fully constitute an ‘internal measure’. Furthermore, physically identical goods with different carbon footprints may be considered as ‘like’ products under GATT, precluding a CBAM that applies to products with the same carbon intensity. The assessment of ‘likeness’ is based on a good’s physical characteristics, end use, consumer preferences and international tariff classification. [47] Given such legal constraints, it may be difficult to privilege burden-sharing justice over harm-avoidance justice, which is more reconcilable with WTO regulations.

Principle of Distributive Justice: Extending John Rawls’ Theory of Justice

John Rawls’ “difference principle” states that rights and responsibilities must be distributed in a manner that improves the conditions of those who are less well-off.[48] CBAM creates disadvantages for developing states without greener, more technologically advanced production processes and carbon taxes. It is likely to have the greatest effects on Least Developed Countries (LDCs) such as Mozambique, which have high levels of energy-intensive exports to the EU. Although LDCs account for less than 0.1% of the imports covered by CBAM, the foreign exchange earnings from such exports to the EU constitute a significant share of their GDP (Figure 6). [49] The loss in trade volume would thus result in a moderate to large negative effect on LDCs GDP in the order of 1.5% to 8.4%. [50] Moreover, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) estimates that a CBAM pegged to a carbon price of $44 per tonne would cause the income of developing countries to drop by $5.9 billion, while increasing that of developed countries by $2.5 billion. [51]

At the same time, CBAM could increase the amount of pollution in developing countries. It stimulates resource reshuffling, whereby third-country producers export products with low carbon content to the EU, while reserving carbon-intensive products for domestic or non-EU markets. [52] This would adversely affect the well-being of less developed countries outside the EU. CBAM thus undermines the position of the least-advantaged countries, violating Rawls’ “difference principle”.

Durability of CBAM: Passing the Ethical Test or Going Up In Smoke

Primacy of Harm-Avoidance Justice

The strength of CBAM’s ethical justifications depends on the relative weight placed on harm-avoidance, burden-sharing, and distributive justice. The sustainability condition states that a climate justice theory should be sidelined if the environmental costs of implementing it are too high. [53] Fundamentally, considering the existential stakes involved in climate change, the world must adopt an all-hands-on-deck approach. It is morally sound to strive for efficiency in reducing global emissions, since ethics should not hinder effective climate action but facilitate it. Therefore, although burden-sharing and distributive justice are morally valid, harm-avoidance justice should take precedence. [54]

Ability to Pay Principle (ATP) as the Middle Ground

In practice, arguing for a full-fledged harm-avoidance approach may not be viable, since countries will continue to cite historical responsibility and global inequalities as justifications for climate inaction. Hence, the tactic of least-harm is to promote a balance between equity and efficiency. This makes ATP the most ethically convincing argument for persuading countries across the political spectrum to take necessary action. ATP is not only fair, but also the most efficient method of distributing the costs of climate change in a way that minimises harm. [55] It circumvents the impracticalities of determining causal historical liability (which PPP does) and the benefits gained by emitters (which BPP involves), and promotes the most effective climate action by inducing less-developed countries to participate in climate efforts where they can. While some may aver that ATP is unfair because a country should not be liable for another country’s negligent pollution, increasing the likelihood of survival could be a more pressing moral obligation than the imperative of burden-sharing justice. Though harm-avoidance justice is the ideal, CBAM is justifiable if the policy at least fulfils ATP.

Ability to Pay Principle (ATP) Requires Equal Relative Sacrifice

While ATP does not necessitate equal reduction in per capita emissions, it advocates that each country bears equal costs, in that populations should sacrifice as much of living standards as they can afford to combat climate change. [56] An endemically poor country should not be mandated to bear any cost since its population has yet to attain a minimum standard of living from which it can sacrifice. However, beyond that, each country – poor or rich – should sacrifice the same in relative terms. This warrants a CBAM that is applied on a case-by-case basis rather than universally. Some have suggested for CBAM to exempt exports from the 23 lower-middle-income countries under the EU’s Generalised System of Preferences schemes, which provide preferential access to the EU market. Since the carbon emissions imported from developing countries only contribute a small proportion of the total emissions in the EU’s final demand, such exemptions would not materially vitiate the EU’s emission reduction efforts. [57]

Limited Ethical Grounds for CBAM

CBAM only secures a weak justification based on harm-avoidance justice: its level of emission reduction is marginal, yet its immediate welfare costs are palpable. The European Commission predicted that CBAM will reduce emissions in the sectors it covers by 1% in the EU and by 0.4% in the rest of the world by 2030. The initial introduction of a CBAM of $44 per tonne would cause developed countries to experience a welfare loss of around $51 billion, due to losses in the EU. When considering burden-sharing justice frameworks, CBAM also has few justifications. In the short run, PPP would make highly polluting companies pay through their loss of market shares, but this would be limited to companies who export their products to the EU. However, in the long run, CBAM transgresses the principle of distributive justice, as it makes developed countries better-off at the expense of developing countries. A research by the Task Force on Climate, Development and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) reports that at its broadest scope of implementation, the EU CBAM could result in an annual welfare gain in developed countries of US$141 billion while developing countries could see an annual welfare loss of US$106 billion. [58] In sum, implementing CBAM seems to have a weak ethical defence.

Endnotes

[1] KPMG. “EU: European Parliament adopts rules for carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM).” KPMG Insights, 2023, https://kpmg.com/us/en/home/insights/2023/04/tnf-eu-rules-for-carbon-border-adjustment-mechanism.html. Accessed 6 July 2023.

[2] European Council. “‘Fit for 55’: Council adopts key pieces of legislation delivering on 2030 climate targets.” European CouncilPress Release, 2023, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2023/04/25/fit-for-55-council-adopts-key-pieces-of-legislation-delivering-on-2030-climate-targets/?utm_source=dsms-auto&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=%27Fit%20for%2055%27%3A%20Council%20adopts%20key%20pieces%20of%20legislation%20delivering%20on%202030%20climate%20targets. Accessed 6 July 2023.

[3] Benson, Emily et al. “Analysing the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism.” Centre for Strategic and International Studies, 2023, https://www.csis.org/analysis/analyzing-european-unions-carbon-border-adjustment-mechanism. Accessed 6 July 2023.

[4] Direct emissions (Scope 1) are produced by the combustion of fossil fuels or carbon-emitting processes in upstream (e.g., extraction of raw materials) and production stages. Meanwhile, indirect emissions (Scope 2) are generated from the use of electricity. See: Sandbag and E3G. “A storm in a teacup: Impacts and geopolitical risks of the European Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism.” Sandbag – Smarter Climate Policy, 2021, https://sandbag.be/wp-content/uploads/E3G-Sandbag-CBAM-Paper.pdf. Accessed 6 July 2023.

[5] Figures, Tim et al. “The EU’s Carbon Border Tax Will Redefine Global Value Chains.” Boston Consulting Group, 2021, https://www.bcg.com/publications/2021/eu-carbon-border-tax. Accessed 6 July 2023.

[6] Ramseur, Jonathan L. et al. “Border Carbon Adjustments: Background and Developments in the European Union.” Congressional Research Service, 2023,

https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R47167. Accessed 6 July 2023.

[7]Campbell, Erin et al. “Border Carbon Adjustments 101.” Resources for the Future, 2021, https://www.rff.org/publications/explainers/border-carbon-adjustments-101/. Accessed 6 July 2023.

[8] European Commission. “Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism.” European Commission, 2023, https://taxation-customs.ec.europa.eu/carbon-border-adjustment-mechanism_en. Accessed 6 July 2023.

[9] Ambec, Stefan. “The European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism: Challenges and Perspectives.” Toulouse School of Economics, 2022.

[10] Keen, Michael et al. “Border Carbon Adjustments: Rationale, Design and Impact.” Institute for Fiscal Studies, 2022, vol. 43, no. 3, 203 – 219.

[11] Hufbauer, Gary Clyde. “Why is the EU seeking a carbon border tax adjustment and how would it work?” Peterson Institute for International Economics, 2021, https://www.piie.com/research/piie-charts/why-eu-seeking-carbon-border-tax-adjustment-and-how-would-it-work. Accessed 6 July 2023.

[12] Bond, David E. et al. “The EU Agreement on a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism.” White & Case, 2023, https://www.whitecase.com/insight-alert/eu-agreement-carbon-border-adjustment-

mechanism. Accessed 6 July 2023.

[13] European Commission. “Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism.” European Commission, 2023, https://taxation-customs.ec.europa.eu/carbon-border-adjustment-mechanism_en. Accessed 6 July 2023.

[14] Manthey, Ewa and Patterson, Warren. “How the EU’s carbon border tax will affect the global metals trade.” ING Think, 2023, https://think.ing.com/articles/how-will-the-eus-carbon-border-tax-affect-global-metals-trade/. Accessed 6 July 2023.

[15] Under the current EU ETS system, free allowances are distributed to EITE sectors to preserve their competitiveness and prevent carbon leakage. While this has been effective in addressing the risk of carbon leakage, it has dampened the incentive to reduce emissions and invest in greener production within the EU and abroad. The CBAM is thus conceived as an alternative to this.

[16] European Commission. “Questions and Answers: Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM).” European Commission Memo, 2023, https://taxation-customs.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2023-06/20230602%20Q%26A%20CBAM.pdf. Accessed 6 July 2023.

[17] Eckersley, Robybn. “The Politics of Carbon Leakage and the Fairness of Border Measures.” Ethics & International Affairs, 2010, vol. 24, no. 4, 367 – 393.

[18] Bellora, Cecilia and Fontagné, Lionel. “EU in search of a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism.” Energy Economics, 2023, vol. 123.

[19] De Cendra, Javier. “Can Emissions Trading Schemes be Coupled with Border Tax Adjustments? An Analysis vis-à-vis WTO Law.” Review of European Community & International Environmental Law, 2006, vol. 15, no. 2, 131 – 244.

[20] Marcu, Andrei. et al. “Addressing Carbon Leakage in the EU: Making CBAM work in a Portfolio of Measures.” European Roundtable on Climate Change and Sustainable Transition, 2021.

[21] Caney, Simon. “Two Kinds of Climate Justice: Avoiding Harm and Sharing Burdens.”, Journal of Political Philosophy, 2014, vol. 22, no. 2, 125 – 149.

[22] Broome, John. Climate Matters: Ethics in a Warming World. New York: W.W. Norton, 2012.

[23] Le Merle, Kevin. “From Burden-Sharing Justice to Harm-Avoidance Justice: Reimagining the EU’s Approach to Climate Justice.” Duodecim Astra – College of Europe Student Journal, 2021, no. 1, 164 – 178.

[24] Simmões, Henrique Morgado. “EU carbon border adjustment mechanism: Implications for climate and competitiveness.” European Parliamentary Research Service, 2023.

[25] Marcu, Andrei. et al. “Addressing Carbon Leakage in the EU: Making CBAM work in a Portfolio of Measures.” European Roundtable on Climate Change and Sustainable Transition, 2021.

[26] Beaufils, Timothé. “Assessing different European Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism implementations and their impact on trade partners.” Communications Earth and Environment, 2023, vol. 4, no. 131.

[27] Gatzen, Christoph et al. “Carbon border taxes – help or harm to European industry?” Frontier Economics, 2023, https://www.frontier-economics.com/uk/en/news-and-articles/articles/article-i7771-carbon-border-taxes-help-or-harm-to-european-industry/#. Accessed 6 July 2023.

[28] The Financial Times Editorial Board. “The EU’s pioneering carbon border tax.” The Financial Times, 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/b1c2055c-15ec-4f29-9227-1a4bfa21bcea. Accessed 6 July 2023.

[29] Adler, Matthew D. and Treich, Nicholas. “Prioritarianism and Climate Change.” Environment Resource Economics, 2015, vol. 52, 279 – 308.

[30] Frankfurt, Harry. “Equality as a Moral Ideal.” Ethics, 1987, vol. 98, 21 – 42.

[31] Baer, Paul. “The greenhouse development rights framework for global burden sharing: reflection on principles and prospects.” WIREs Climate Change, 2013, vol. 4, no. 1, 61 – 71.

[32] Caney, Simon. “Two Kinds of Climate Justice: Avoiding Harm and Sharing Burdens.” Journal of Political Philosophy, 2014, vol. 22, no. 2, 125 – 149.

[33] Heine, Dirk et al. “The polluter-pays principle in climate change law: An economic appraisal” Climate Law, 2020, vol. 10, no. 1, 94 – 115.

[34] Massenberg, Julian Richard. “Global Climate Change—Who Ought to Pay the Bill?” Sustainability, 2021, vol. 13, no. 23, 1 – 14.

[35] Ülgen, Sinan. “A Political Economy Perspective on the EU’s Carbon Border Tax.” Carnegie Europe, 2023, https://carnegieeurope.eu/2023/05/09/political-economy-perspective-on-eu-s-carbon-border-tax-pub-89706. Accessed 6 July 2023.

[36] Ritchie, Hannah. “Who has contributed most to global CO2 emissions?” The World in Data, 2019, https://ourworldindata.org/contributed-most-global-co2. Accessed 6 July 2023.

[37] Lowe, Sam. “The EU’s carbon border adjustment mechanism: How to make it work for developing countries.” Centre for European Reform, 2021,

https://www.cer.eu/sites/default/files/pbrief_cbam_sl_21.4.21.pdf. Accessed 6 July 2023.

[38] Larbprasertporn, Pananya, “The Interaction Between WTO Law and the Principle of Common but Differentiated Responsibilities in the Case of Climate-Related Border Tax Adjustments”, Goettingen Journal of International Law, 2014, vol. 6, no. 1, 145 – 170.

[39] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. “Can the Warming of the 20th Century be Explained by Natural Variability?”, 2007, https://archive.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/ar4/wg1/en/faq-9-2.html. Accessed 6 July 2023.

[40] Caney, Simon. “Climate change and the duties of the advantaged.” Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy, vol. 13, no.1, 216 – 217.

[41] Shue, Henry. “Global Environment and International Inequality.” International Affairs, 1999, vol. 75, no. 3, 531 – 545.

[42] The African Climate Foundation and Firoz Lalji Institute for Africa. “Implications for African Countries of a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism in the EU.” African Climate Foundation and The London School of Economics and Political Science, 2023.

[43] Kirby, Robert. “The Beneficiary Pays Principle and Climate Change.” The Australian National University, 2016.

[44] Heyward, Clare. “Is the beneficiary pays principle essential in climate justice?” Norsk filosofisk tidsskrift, 2021, vol. 56, 125 – 136.

[45] Emerson, Craig and Moritsch, Stefano. “Making Carbon Border Adjustment proposals WTO-compliant.” KPMG, 2021, https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/xx/pdf/2021/03/making-carbon-border-adjustment-proposals-wto-compliance.pdf. Accessed 6 July 2023.

[46] Leonelli, Giulia Claudia. “Export Rebates and the EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism: WTO Law and Environmental Objections.” Journal of World Trade, 2022, vol. 46, no. 6.

[47] Davies, Arwel. “The EU’s Proposed Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism and Compatibility with WTO Law.” Trade, Law and Development, 2022, vol. 14, no. 2.

[48] Li, Gloria. “Rawls, Climate Change, and Essential Goods.” Acta Cogitata: An Undergraduate Journal in Philosophy, 2019, vol. 7, no. 4, 1 – 9.

[49] Tripathi, Bhasker. “How will the EU’s new carbon tax affect developing nations?” Context, 2023, https://www.context.news/net-zero/how-will-the-eus-new-carbon-border-tax-affect-developing-nations. Accessed 6 July 2023. .

[50] Pleeck, Samuel et al. “An EU Tax on African Carbon – Assessing the Impact and Ways Forward.” Centre for Global Development, 2022, https://cgdev.org/blog/eu-tax-african-carbon-assessing-impact-and-ways-forward. Accessed 6 July 2023.

[51] United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. “EU should consider trade impacts of new climate change mechanism.” United Nations Conference on Trade and Development News, 2021, https://unctad.org/news/eu-should-consider-trade-impacts-new-climate-change-mechanism. Accessed 6 July 2023.

[52] Simmões, Henrique Morgado. “EU carbon border adjustment mechanism: Implications for climate and competitiveness.” European Parliamentary Research Service, 2023.

[53] Caney, Simon. “Just Emissions.” Philosophy and Public Affairs, 2012, vol. 40, no. 4.

[54] Le Merle, Kevin. “From Burden-Sharing Justice to Harm-Avoidance Justice: Reimagining the EU’s Approach to Climate Justice.” Duodecim Astra – College of Europe Student Journal, 2021, no. 1, 164 – 178.

[55] Ibid.

[56] Le Merle, Kevin. “From Burden-Sharing Justice to Harm-Avoidance Justice: Reimagining the EU’s Approach to Climate Justice.” Duodecim Astra – College of Europe Student Journal, 2021, no. 1, 164 – 178.

[57] Lowe, Sam. “The EU’s carbon border adjustment mechanism: How to make it work for developing countries.”, Centre for European Reform, 2021, https://www.cer.eu/sites/default/files/pbrief_cbam_sl_21.4.21.pdf. Accessed 6 July 2023.

[58] Xiaobei, He et al. “The Global Impact of a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, A Quantitative Assessment.” Task Force on Climate, Development and the International Monetary Fund, 2022, https://www. bu.edu/gdp/files/2022/03/TF-WP-001-FIN.pdf.

Photo courtesy of Filmbetrachter at pixabay.com