The Failure of Silicon Valley Bank

By Mai Huynh

Silicon Valley Bank’s failure evokes unsettling parallels to the 2008 financial crisis. Just as Lehman Brothers’ bankruptcy was a defining moment in the 2008 crisis, the failure of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) represents a major setback for the banking sector, particularly due to its significant presence and influence in Silicon Valley, a global hub of technological innovation. With total assets reaching $218 billion, Silicon Valley Bank secured its position as the 16th largest bank in the U.S. (Vo & Le, 2023). Given the bank’s reputation as one of the nation’s top national and regional banks, the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank came as a surprise to many investors and industry experts.

Background

The bank’s journey since it established in 1983 has been marked by remarkable growth, defying even the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite its success, Silicon Valley Bank stood as an outlier in the banking industry, primarily due to its highly concentrated business model (Barr, 2023). While the bank expanded its services to include asset management, private wealth management, investment banking, M&A advisory services, and other investment offerings over time, its core focus remained on supporting innovation and entrepreneurship in the technology and life sciences sectors (Vo & Le, 2023). Silicon Valley Bank catered specifically to the banking needs of tech startups, acting as a vital source of capital for early-stage companies. The bank served numerous VC firms as clients. Silicon Valley is home to over 50% of all U.S. venture-backed companies. This distinctive business model aligns with the description provided by Silicon Valley historian Margaret O’Mara, who refers to Silicon Valley Bank as “a community bank.” (Morrison, 2023). Joining the bank was like entering a network that fostered and assisted entrepreneurs through periods of growth and adversity (Epstein, 2023). Even with the trust of the Silicon Valley community, the bank faced a sudden collapse within a span of two days in March 2023. A closer examination reveals that the bankruptcy can be attributed to a combination of factors, including poor risk management practices, significant exposure to interest rate risk, and the detrimental impact of social media attention.

1. Risky Business: Mismanagement and Interest Rates

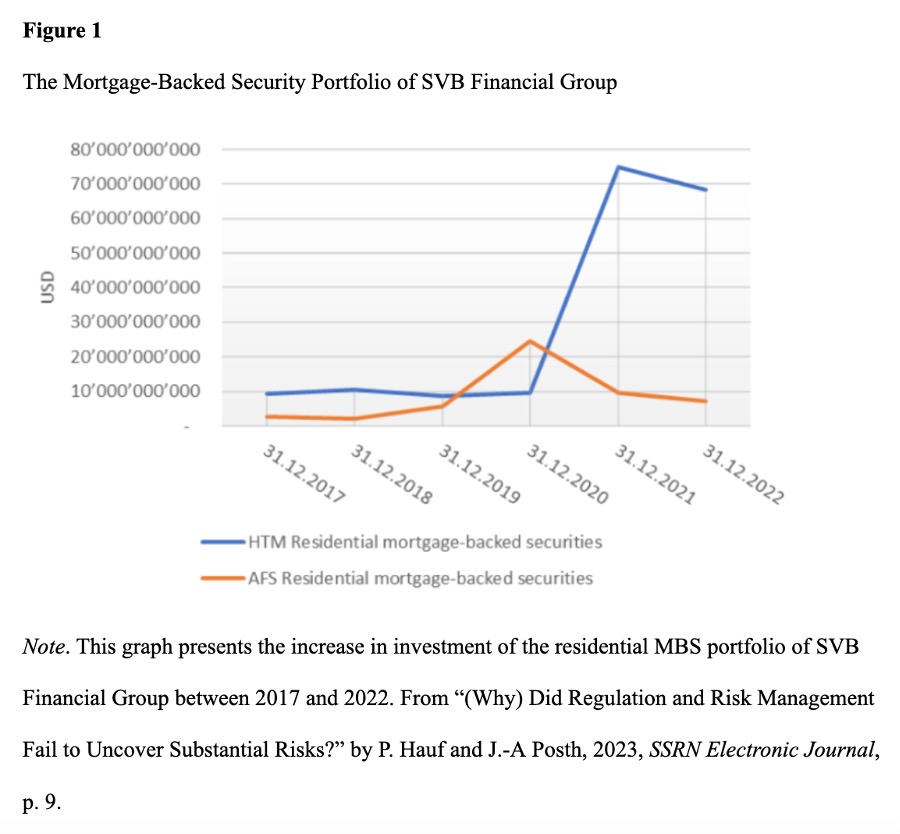

Silicon Valley Bank initially appeared to be a thriving and successful institution. According to the bank’s 10-Q report, its financial position surpassed the regulatory minimum, with no bad loans or involvement in risky enterprises (Mérő, 2023). However, a closer look at the bank’s balance sheet revealed a different story, particularly regarding its heavy investment in Treasury bonds and U.S. government agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS). Figure 1 illustrates the significant growth of the bank’s investment portfolio, particularly the steep increase in its holdings of held-to-maturity (HTM) securities (Hauf & Posth, 2023).

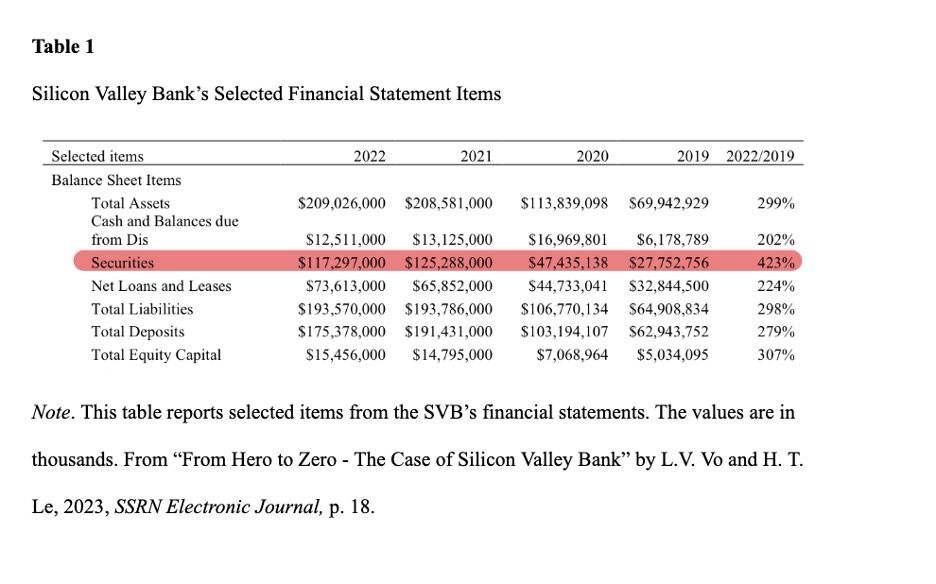

From 2019 to 2022, the bank’s securities investments skyrocketed from $28 billion to $117 billion, demonstrating its reliance on leveraging low-interest bonds to maximize yield and interest income (See Table 1). The majority of these bonds were held-to-maturity assets, meaning the bank did not intend to sell them in the near future and therefore did not mark them to market on the balance sheet. This strategy proves effective during periods of economic growth, as it poses low risks while still generating interest income from a large number of investments. However, it also exposes the bank to significant interest rate risk when the market experiences a downturn.

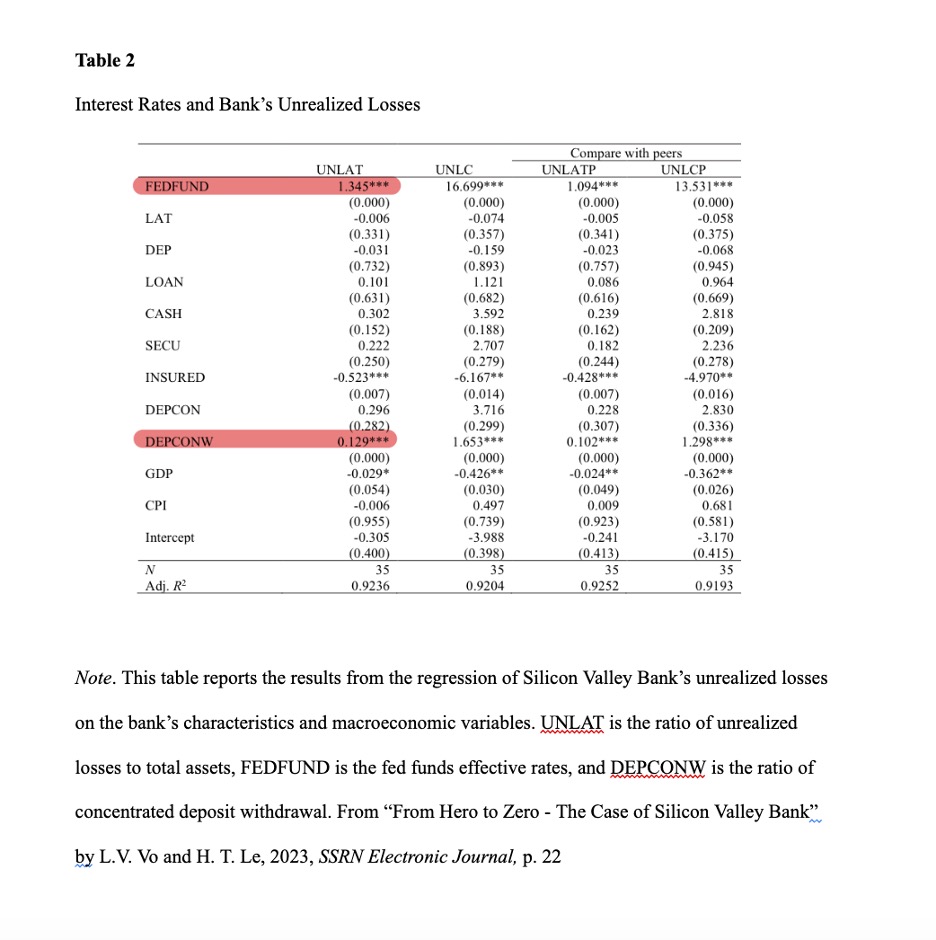

Unfortunately, this precisely happened to Silicon Valley Bank. After the first quarter of 2022, to maintain price stability and minimize inflation rates, the Federal Reserve started raising interest rates periodically. Interest rates began to rise to 0.5% in March 2022 and gradually increased to 4% in November 2022. As a result, instead of earning income from its HTM securities, the interest rate hike implemented by the Federal Reserve diminished the value of the bank’s bonds. Table 2 displays the regression results on the bank’s ratio of unrealized losses to total assets, showing a positive and significant correlation between interest rates (FEDFUND) and the bank’s unrealized losses (UNLAT). In other words, as interest rates increased, the bank incurred higher unrealized losses even after accounting for bank characteristics and other macroeconomic variables. This result held true as the bank’s substantial holdings of debt securities led to significant unrealized losses, amounting to at least 14.80% of the value of debt securities totaling $125 billion.

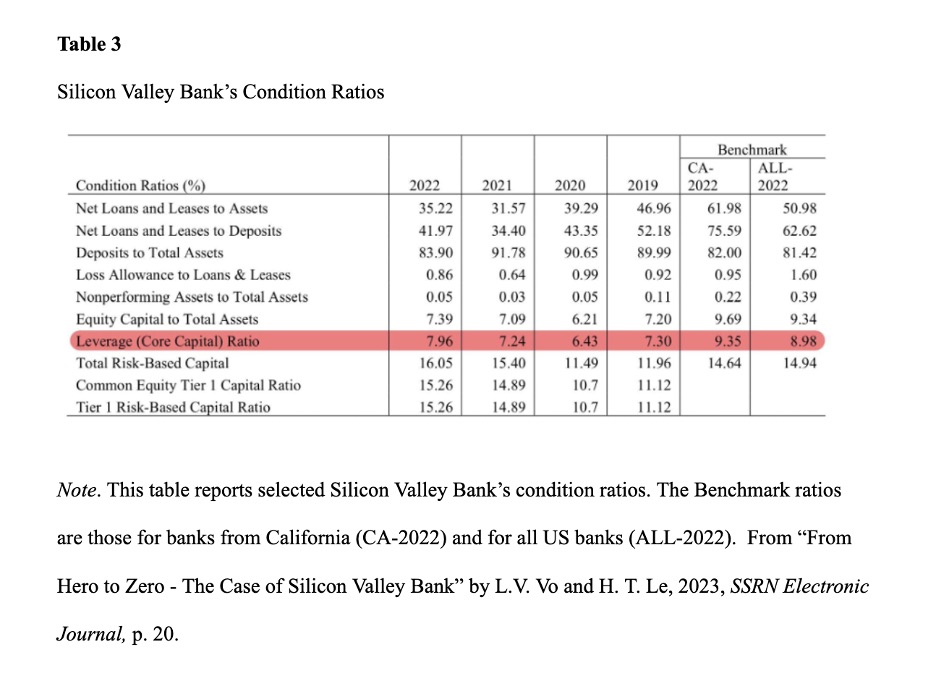

As news spread about the decline in the bank’s bond holdings, depositors grew concerned and withdrew their funds. To meet the sudden withdrawals, the bank was forced to sell its bonds, reclassifying them as “Available-for-Sale” (AFS) rather than “Hold-to-Maturity” (HTM). This decision crystallized the losses and marked them down on the bank’s financial statements, intensifying depositors’ worries. The severity of this issue could have been alleviated if the bank had maintained a higher ratio of equity capital to total assets. Despite the bank’s ratio of equity capital to total assets remaining relatively stable from 2019 to 2022, ranging from 7.30% to 7.96%, it still falls below the industry average of 8.98% (See Table 3). This lower ratio suggests that a decline in asset prices has the potential to erode the bank’s equity. While the strategy of relying on borrowed funds from depositors to finance investments can enhance profits during periods of growth and economic prosperity, inadequate management of these investments can expose the bank to financial instability during downturns.

2. The Price of Dependence: The Downfall of High Concentration

There were concerns the failure of Silicon Valley Bank would trigger a domino effect, potentially leading to a series of bank failures. However, most experts agree the bank’s collapse should be regarded as an exceptional circumstance resulting from poor management that encountered multiple challenges simultaneously (Ordonez, 2023). The bank’s heavy concentration of clients in a single sector and region played a pivotal role. While the rapid growth of the tech industry in Silicon Valley initially fueled the bank’s success, it also rendered the institution highly susceptible to the volatility of the venture capital sector and the Northern California region. Consequently, when the businesses in the sector panicked, the bank suffered as well, highlighting the lack of depositor diversification.

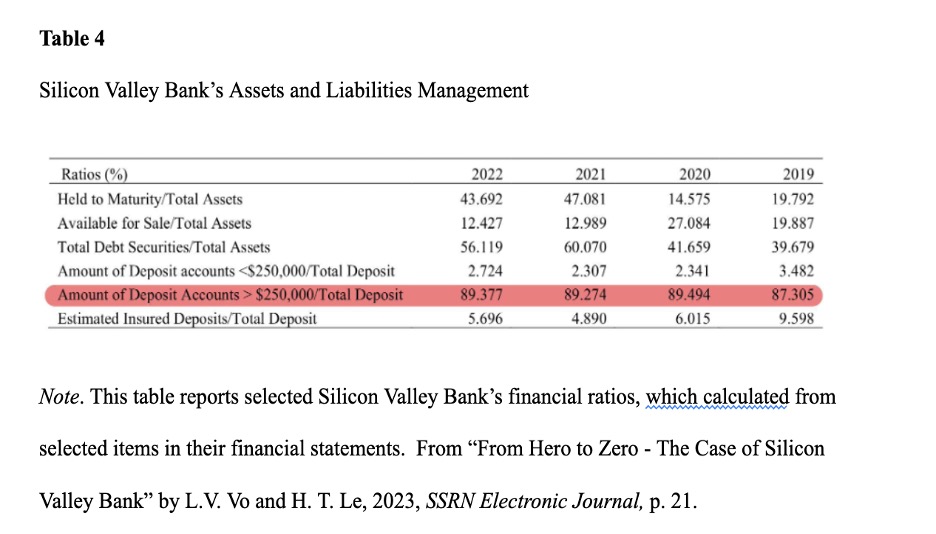

A closer analysis at the bank’s financial statements revealed a concerning reliance on a small percentage of depositors. In 2022, 89.3% of the bank’s total deposits originated from accounts exceeding the FDIC-insured limit of $250,000 (See Table 4). This unexpectedly high figure can be attributed to Silicon Valley Bank’s practice of rewarding depositors who kept all their funds with the bank (Epstein, 2023). The bank offered preferential treatment, including favorable loan terms and services, to clients who kept all their financial assets with them.

This concentration of deposits underscores the importance of diversification of the client base. The bank’s failure serves as a stark reminder that relying solely on a single industry sector can have detrimental consequences, potentially leading to bankruptcy unless the FDIC steps in to insure all deposits. Furthermore, this concentration of depositors rendered the bank exceptionally vulnerable to the threat of a bank run. Referencing back to Table 2 above, multivariate analysis suggests the withdrawal of concentrated deposits (DEPCONW) had a significant impact on unrealized losses of total assets (UNLAT).

Arguably, the concentration of venture capital clients indirectly exposed Silicon Valley Bank to significant interest rate risk. Given the rapid growth of the startup sectors, a substantial influx of investor cash flowed into these startups, resulting in a surplus of deposits at the bank. As these startups had limited borrowing needs, and the bank had few opportunities for traditional banking use, the accumulated deposits created a surplus of funds. In response to this surplus, Silicon Valley Bank made the decision to heavily invest in Treasury bonds and U.S. government agency mortgage-backed securities. This move was motivated by the rapid growth in deposits that outpaced loan growth, as stated by SVB Financial Group: “rapid deposit growth has exceeded the pace of our loan growth, and as a result, a significant amount of excess deposits not used to fund loan growth have contributed to the growth of investment balances” (Hauf & Posth, 2023).

3. The Power of Online Panic: Silicon Valley Bank Run

While the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank can be attributed as a textbook case of inadequate risk management practices, the rapid spread of news on social media significantly accelerated the bank run process. As interest rates continued to rise after March 2022, clients of Silicon Valley Bank withdrew funds to fulfill their liquidity requirements. Consequently, Silicon Valley Bank needed to find ways to accommodate these customer withdrawals. Unfortunately, this necessitated the sale of $21 billion loss-making securities portfolio. The portfolio, yielding at 1.79%, fell considerably short of the then 10-year Treasury yield of approximately 3.9%. As a result of the decline in bond value, the bank incurred a loss amounting to $1.8 billion. On March 8, Silicon Valley Bank made a significant announcement regarding its financial position. To bolster its balance sheet, the bank disclosed its intention to sell $2.25 billion worth of shares (SVB Financial Group, 2023).

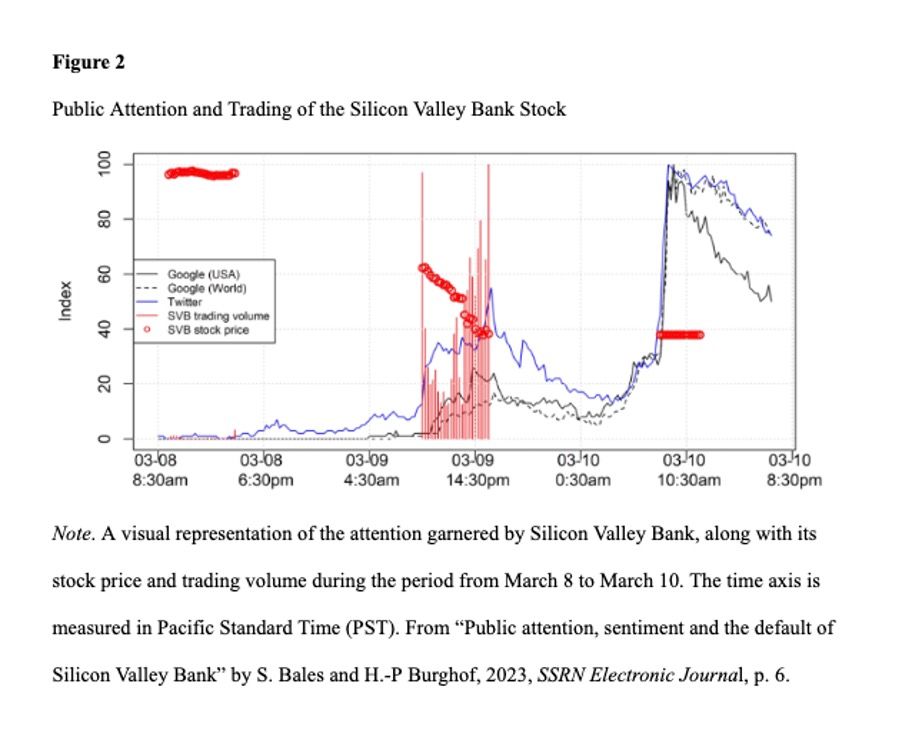

The timing of this announcement proved detrimental. In this digital era, X (formerly known as Twitter) stands as a prominent source of news, with many investors relying on this medium for information. Additionally, a significant portion of Silicon Valley Bank’s customer base held account balances exceeding the standard maximum FDIC-insured amount of $250,000, making these customers particularly susceptible to the panic and fear spread online. The concern about the potential spread of panic was well-founded, with even the Vice Chair for Supervision of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Michael Barr, acknowledging that social media enabled depositors to instantly spread concerns about a bank run. As a result, the announcement about the sale on March 8 triggered a wave of panic, leading to the withdrawal of $42 billion in deposits on March 9 (Bales & Burghof, 2023).

Figure 2 provides stock price and volume movements of Silicon Valley Bank shares, during the period from March 8 to March 10. The graph clearly illustrates the accumulation of attention during non-trading hours, followed by a flurry of trading activity once the markets reopened on March 9. This sudden surge in trading activity contributed to the abrupt decline in the bank’s stock price. As Haulf and Posth say, every bank is on the brink of failure as soon as trust in the solvency and liquidity vanishes (Hauf & Posth, 2023). By March 10, Silicon Valley Bank’s stock had plummeted by 61.2%, prompting the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) to announce the closure of the bank.

Intervention: Government’s Dilemma in Responding to Bank Collapse

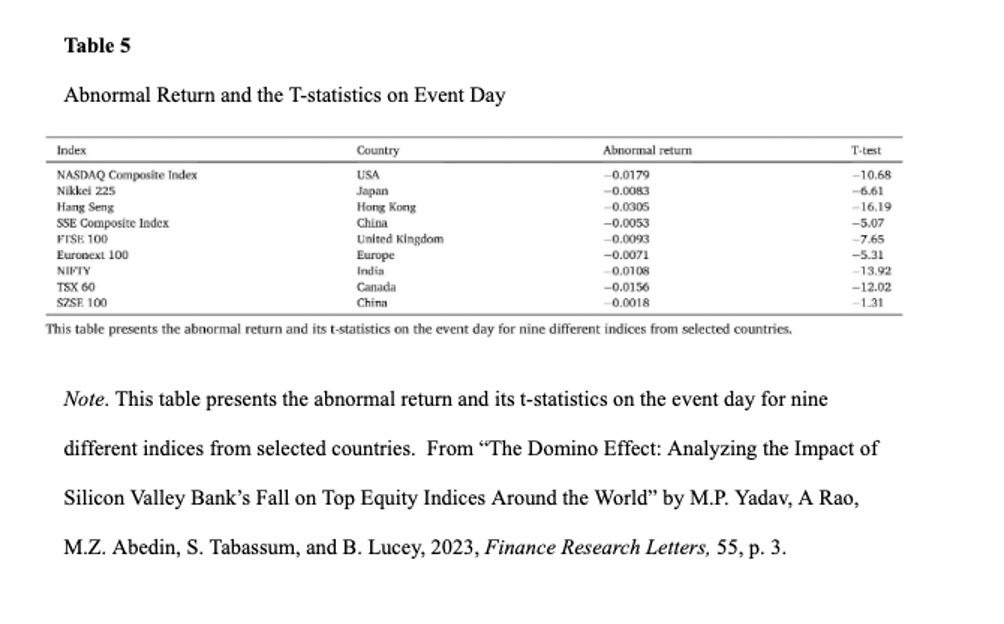

With mounting concerns surrounding the fate of Silicon Valley Bank, the question of whether government intervention was warranted to protect and stabilize the institution becomes increasingly relevant. The interconnected nature of financial institutions underscores the potential ripple effects that can arise from the failure of a major player in the banking sector. Not only can it lead to a regional banking crisis, but it also has the capacity to significantly impact global equity markets and the overall evaluation of banks worldwide. These concerns are supported in the study presented in Table 5, which examines the performance of equity exchanges in seven countries or regions. The findings reveal negative returns for each of the indices, highlighting the market’s response to the uncertainties surrounding Silicon Valley Bank. It is worth noting the extent of these negative abnormal returns varies across different stock exchanges. For instance, the Hang Seng exchange experienced the most pronounced negative abnormal return, with a significant decline of 3.05%. Conversely, the SZSE 100 showed a relatively minimal impact with a negative abnormal return of only -0.18% (Yadav et al., 2023). At that time, there was uncertainty about the regional impact of Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse on depositor and citizen confidence. The repercussions of the bank’s failure were clearly reflected in the stock market. In the following week, stocks of more than two dozen regional banks experienced a significant decline, reflecting the concerns and uncertainties surrounding the banking sector (Ordonez, 2023).

After the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, the government took swift action to contain the damage and prevent a domino effect in the financial sector. The Federal Reserve, the FDIC, and the Treasury Department intervened by declaring all deposits safe, reassuring depositors, and halting the potential spread of panic (Barr, 2023). Commentators have suggested the pleas of influential venture capitalists played a role in the government’s decision to protect deposits, highlighting their influence on the Biden administration (Morrison, 2023). Some pointed out the hypocrisy of those who urged the government to protect deposits as they were the same individuals who opposed bailing out student loan borrowers. The government’s intervention may be attributed to the desire to avoid a repetition of the 2008 financial crisis, namely the systemic collapse and the potential for a widespread banking crisis.

In addition to providing insurance for depositors’ funds, the government also took steps to address the aftermath of a bank collapse. In the case of Silicon Valley Bank, a thorough investigation was launched to determine the causes and circumstances that contributed to the failure. On April 28, 2023, a report authored by Michael Barr, Vice Chair of the Federal Reserve, was published (Barr, 2023). This report shed light on the challenges faced by the bank and serves as a roadmap to enhance the banking sector’s stability.

An Ethics Discussion of the Collapse

- Fairness and Transparency

Government intervention following the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank raises ethical concerns. While the intervention aimed to protect depositors and safeguard the financial system, it inevitably gives rise to questions of fairness and moral hazard. The primary concern revolves around the source of funds utilized by the government to make depositors whole. The government may have learned from the handling of the 2008 crisis, where taxpayer money was employed to bail out major financial institutions. The bailout resulted in public criticism and resentment towards banks (Ordonez, 2023 and URBAIN, 2023). A joint statement by Secretary of the Treasury Janet L. Yellen, Federal Reserve Board Chair Jerome H. Powell, and FDIC Chairman Martin J. Gruenberg declared taxpayer funds would not bear any losses associated with the resolution of Silicon Valley Bank (2023) The FDIC employed the Deposit Insurance Fund (DIF) to ensure the restoration of depositors’ funds instead. The DIF is primarily funded through quarterly assessments on insured banks, with contributions coming from the banking industry itself (Ordonez, 2023). It is through this program the regular $250,000 FDIC insurance coverage for depositors originates. As of the end of 2022, the program held a substantial balance of over $100 billion, which amounts to approximately 1.27% of the $10 trillion in insured deposits (URBAIN, 2023). This ample reserve was deemed sufficient to fulfill the commitment of making Silicon Valley Bank depositors whole.

Despite the official joint statements from the FDIC, the Federal Reserve, and the Treasury, doubts regarding the implications of using the Deposit Insurance Fund (DIF) continued. Many remained apprehensive about the potential consequences of depleting the DIF and the eventual burden that could fall upon citizens, as the program is designed to cover insured deposits and will ultimately need replenishment. Former Vice President Mike Pence voiced the public sentiment, expressing concerns that “Every American with a bank account will pay higher fees to replenish the billions spent by the FDIC to backstop failing banks”. Mark Williams, a lecturer at Boston University, added his perspective, noting that while the government’s immediate efforts may have prevented the spread of financial contagion, the long-term cost lies in the increased moral hazard associated with such interventions.

- Moral Hazard

The second concern pertains to the shareholders of Silicon Valley Bank. This concern stems from the fact the Federal Reserve’s interest rate hikes were expected and well-publicized, leaving no excuse for Silicon Valley Bank to be taken by surprise (Epstein, 2023). The government’s decision to bail out the bank could be perceived as rewarding irresponsible behavior. Potentially creating a moral hazard whereby banks feel emboldened to engage in excessive risk-taking with the expectation of a safety net in case of failure. The government swiftly addressed these concerns by clarifying that shareholders of the bank had suffered complete losses. Additionally, certain unsecured debt holders were not protected, and senior managers were removed from their positions (Joint Statement by Treasury, Federal Reserve, and FDIC, 2023). The government’s decisive action in wiping out shareholders’ investments sends a clear signal that future bailouts should not be taken for granted and that firms must bear the consequences of their actions. Nevertheless, despite the government’s efforts to address concerns, there are still those who express dissatisfaction with how the situation was handled. Andrew Ross Sorkin, from the New York Times (NYT) and CNBC, voiced his opinion that the government’s actions constituted bailing out the venture capital community and their portfolio companies, given they form the depositor base of Silicon Valley Bank (Ordonez, 2023). This raises issues of privilege and further highlights the complexities and ethical considerations surrounding the intervention.

- Failure of Regulators

The third concern revolves around regulatory oversight, as regulators have a duty to protect the interests of the public and ensure the stability and integrity of the financial system. In the case of Silicon Valley Bank, regulators appear to have failed in identifying the bank’s overreliance on investment in MBS, its concentration in a single sector, and the fact that a large proportion of its depositors surpass the $250,000 threshold. Policymakers have attributed this regulatory oversight to the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act of 2018 (S. 2155). The S. 2155 legislation aimed to regulate mid-sized banks (Russo, 2023). Prior to the enactment of S. 2155, Silicon Valley Bank would have been subjected to a liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) requirement of 100% due to its consolidated assets exceeding $50 billion. However, under S. 2155, the bank was not subject to the LCR since it did not possess over $50 billion in weighted short-term wholesale funding (wSTWF). Nonetheless, a report by Christopher M. Russo, the Republican Chief Economist, refutes this claim by suggesting that no reasonable bank liquidity requirement could have effectively safeguard against the deposit outflows experienced by Silicon Valley Bank. Meeting a 100% liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) would have only provided a slight reduction in the bank’s illiquidity risk. While regulatory oversight may not be the direct cause of the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, it still is important for regulations to continuously improve to prevent similar bank failures in the future.

- Insider Trading

The fourth concern surrounding the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank is insider trading. Illegal insider trading refers generally to buying or selling a security, in breach of a fiduciary duty or other relationship of trust and confidence, based on material, nonpublic information about the security (Insider Trading). Insider trading raises serious questions about fairness, transparency, and integrity in the financial system as it undermines the level playing field that is crucial for maintaining trust and confidence in the markets. Reportedly, both Gregory Becker, the former CEO of the bank, and Daniel Beck, the former Chief Financial Officer, sold their stock just days before the collapse (Epstein, 2023). Such actions directly betray the trust of those who had faith in the value of Silicon Valley Bank, such as the shareholders.

Navigating Bank Collapse: Lessons from Silicon Valley Bank

The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank serves as a stark reminder of the vulnerability and interconnectedness within the banking sector, particularly when confronted with emerging challenges and unforeseen events. The bank’s rapid growth, fueled by the thriving tech industry in Silicon Valley, led to such success that most industry experts were surprised by its collapse. Few had paid attention to the weaknesses inherent in a highly concentrated business model. Additionally, the bank’s failure can be attributed to various factors, including social media triggering a bank run, inadequate risk management practices, and a significant exposure to interest rate risks.

Following the bank’s collapse, government intervention demonstrated the authorities’ commitment to containing the damage and preventing a broader banking crisis. Many expressed dissatisfaction with the government’s handling of the situation, raising concerns about fairness and the allocation of funds. To prevent similar incidents in the future, it is crucial for banks to enhance risk management practices, diversify depositors, and maintain sufficient equity capital to weather market downturns. Regulators and policymakers must continually refine and adapt regulations to address emerging risks and potential threats to financial stability. Unfortunately, regulators are often in “response mode,” primarily focused on addressing causes of past crises rather than anticipating new issues (URBAIN, 2023).

Work Cited

Bales, S., & Burghof, H.-P. (2023). Public attention, sentiment and the default of Silicon Valley Bank. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4398782

Board of Government of the Federal Reserve System. & Barr, M. S. (2023, April 28). Review of the Federal Reserve’s Supervision and Regulation of Silicon Valley Bank. Retrieved from https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/review-of-the-federal-reserves-supervision-and-regulation-of-silicon-valley-bank.htm

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and Department of the Treasury. (2023, March 12). Joint Statement by Treasury, Federal Reserve, and FDIC. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Retrieved from https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/monetary20230312b.htm.

Epstein, D. (2023, March 14). Silicon Valley Bank: Blame and ethics of the failure. Insights@Questrom. https://insights.bu.edu/silicon-valley-bank-blame-and-ethics-of-the-failure/

Hauf, P., & Posth, J.-A. (2023). Silicon Valley Bank – (why) did regulation and risk management fail to uncover substantial risks? SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4411102

Investor.gov. (n.d.). Insider Trading. Investor.gov | U.S. Securities and Exchange Conmission. https://www.investor.gov/introduction-investing/investing-basics/glossary/insider-trading

Morrison, S. (2023, March 16). What happens to Silicon Valley Without Silicon Valley Bank?. Vox. https://www.vox.com/technology/2023/3/16/23641641/silicon-valley-bank-failure-history

Mérő, K. (2023). Shall we reconsider banking regulations? some lessons drawn from the failure of Silicon Valley Bank and Credit Suisse. Economy & Finance, 10(2), 101–119. https://doi.org/10.33908/ef.2023.2.2

Ordonez, V. (2023, March 15). A bailout or not? Did the federal government bailout Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank?. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/Business/bailout-federal-government-bailout-silicon-valley-bank-signature/story?id=97846142

SVB Financial Group. (2023, March 8). SVB Financial Group announces proposed offerings of common stock and mandatory convertible preferred stock. SVB Financial Group Announces Proposed Offerings of Common Stock and Mandatory Convertible Preferred Stock. https://ir.svb.com/news-and-research/news/news-details/2023/SVB-Financial-Group-Announces-Proposed-Offerings-of-Common-Stock-and-Mandatory-Convertible-Preferred-Stock/default.aspx

United States Congress Joint Economic Committee & Russo, C. M. (2023, May 16). Tailoring Liquidity Rules Did Not Cause the Failure of Silicon Valley Bank. Retrieved from https://www.jec.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/republicans/2023/5/tailoring-liquidity-rules-did-not-cause-the-failure-of-silicon-valley-bank#:~:text=This%20report%20explains%20how%20the,142%20billion%20in%20two%20days).

URBAIN, T. (2023, March 21). US Government Seeks To Avoid “Bailout” Label Amid Banking Turmoil. Barron’s. https://www.barrons.com/news/us-government-seeks-to-avoid-bailout-label-amid-banking-turmoil-677d2ebe

Vo, L. V., & Le, H. T. (2023). From hero to zero – the case of silicon valley bank. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4394553

Yadav, M. P., Rao, A., Abedin, M. Z., Tabassum, S., & Lucey, B. (2023). The domino effect: Analyzing the impact of Silicon Valley Bank’s fall on top equity indices around the world. Finance Research Letters, 55, 103952. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2023.103952

Image courtesy of NYPost